One of Emerson’s friends, who became a contributor to “The Dial” through his influence, was Samuel Gray Ward, son of Thomas Wren Ward, a Boston banker, for many years treasurer of the Boston Athenaeum, and afterwards of Harvard College. The father was, in 1827, made the American agent of the banking house of Baring Brothers of London, and on his retirement many years later, the agency was continued. in the hands of the son. It remained under his direction until 1887, first in Boston, but after 1862 in New York; and during this period of sixty years the agency was conducted. with uniform wisdom and success.

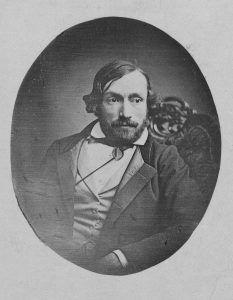

Samuel Gray Ward was born in Boston, October 3, 1817, and graduated at Harvard in 1836. He then spent two years of travel in Europe under fortunate circumstances; and it was on his return, in 1838, that his acquaintance and friendship with Emerson began. He contributed six poems to “The Dial” and four prose articles. Four of the poems were printed in the first number, being the sonnet to W. Allston on seeing his painting called “The Bride,” which was placed immediately after Margaret Fuller‘s article on the “Allston Exhibition;” the song on the next page; and the poems called “The Shield” and “Come Morir,” placed before and after “The Problem” of Emerson. In the third number of the first volume appeared Ward’s “Letters from Italy on the Representatives of Italy,” which were devoted to the discussion of the influence of Boccaccio on Italian literature and character. Near the end of the second number of the third volume was printed a dialogue by Ward, called “The Gallery,” which discussed the true principles of art. In the first number of the fourth volume appeared “Notes on Art and Architecture,” and in the third number an article on the “Translation of Dante,” reviewing T. W. Parsons’ translation of the first ten cantos of “The Inferno.” The last number contained “The Twin Loves” and “The Consolers,” poems by Ward. Emerson included in his “Parnassus” “The Shield” and “The Consolers,” but without Ward’s name.

In a personal letter Ward says of his connection with “The Dial”: “The only literary interest attaching to my name in this connection grows out of my early intimacy with the founders of “The Dial,” — Margaret Fuller, whom I knew from 1835, and R. W. Emerson a year or two later; and with the other writers who made so great a name in the following decades. The thirty years and more of my active life were devoted to business, which left no time for literary work, even supposing that I had the literary gift, which, as it never manifested itself in such surroundings, may be doubted.” However, Ward contributed an essay on “Criticism” to Miss Peabody’s “Æsthetic Papers,” and, in 1840, he published in Boston a volume of translations from Goethe, entitled “Essays on Art.” It was at one time proposed that he should prepare a part of the memoirs of Margaret Fuller, which were finally written by Emerson, Clarke, and W. H. Channing. Higginson prints in his biography of her a letter to Ward, in which she speaks in glowing words of her interest in the various phases of nature. Emerson found in Ward a devoted friend, and his letters to Ward have been edited by Professor Charles Eliot Norton as “Letters from Ralph Waldo Emerson to a Friend, 1838-1853.” Norton says of these letters: “The letters and fragments of letters here printed are part of the early records of a friendship which, beginning when Emerson was thirty years old, lasted unbroken and cordial till his death. . . . The friend was younger than Emerson by nine years. At the beginning of their friendship he had lately returned from Europe, where he had spent a year and a half under fortunate conditions. The youth had brought back from the Old World much of which Emerson, with his lively interest in all things of the intelligence, was curious and eager to learn. His own genius was never more active or vigorous, and his young friend’s enthusiasm was roused by the spirit of Emerson’s teaching. . . . He did not fall into the position of a disciple seeking from Emerson a solution of the problems of life; but he brought to Emerson the highest appreciation of the things which Emerson valued, and knowledge of other things of which Emerson knew little but for which he cared much.”

While in Europe Ward had devoted himself largely to the study of art, especially painting and architecture; and it was in this field of knowledge that Emerson learned most from his friend. In one of the earlier of the letters Emerson refers to a portfolio of sketches loaned him by his friend. Ward gave him one of these, and Emerson expressed his reluctance to separate it from “its godlike companions to put it where it must shine alone.” In his “Ode to Beauty” Emerson refers to his art studies with Ward:

Which hold the grand designs

Of Salvator and Guecino,

And Piranesi’s lines.”

The friends exchanged books, Emerson sending Thoreau’s “Elegy,” and his own essay on “Friendship.” Concerning the latter he wrote: “I am just now finishing a chapter of friendship (of which one of my lectures last winter contained a first sketch) on which I would gladly provoke a commentary. I have written nothing with more pleasure, and the piece is already indebted to you and I wish to swell my obligations.” This correspondence did not continue beyond 1853, doubtless in part because the friends often met for a number of years after that date. What the friendship was to Emerson is indicated by his saying in one of his letters: “The reason why I am curious about you is that with tastes which I also have. you have tastes and powers and corresponding circumstances which I have not and perhaps cannot divine.” In one of his letters to Carlyle, in 1843, Emerson wrote of Ward as cc my friend and the best man in the city, and. besides all his personal merits, a master of all the offices of hospitality.” In fact, Ward was eminently a clubbable man, and he was not only a member of the transcendental club, but of the Town and Country Club that succeeded it for a short time in 1849. He was also connected with the beginnings of the Saturday Club, the most prominent and successful of the literary clubs of Boston. Concerning its formation Richard Henry Dana, the younger, said: “The club had an accidental origin. in a habit of Emerson, Dwight, Whipple, and one or two more dining at Woodman’s room at Parker’s occasionally. Ward is a friend of Emerson’s, and came.”

In one of his letters to Ward Emerson mentions his having invited Longfellow and Lowell to join the club, and their interest in it; also he speaks of Lowell’s enthusiasm in regard to the publication of a magazine, “The Atlantic Monthly” finally being the result.

After his retirement from business, in 1887, Ward became a resident of Washington, where he is still living.

—George Willis Cooke, A Historical

and Biographical Introduction to the Dial

(Cleveland: Rowfant Club, 1902) v. 2, pp. 36-39

From The Dial:

- No. I (Vol. I., no. 1): July 1840:

- No. III (Vol. I., no. 3): January 1841:

- No. X (Vol. III., no. 2): October 1842:

- No. XIII (Vol. IV., no. 1): July 1843:

- No. XV (Vol. IV., no. 3): January 1844:

- No. XVI (Vol. IV., no. 4): April 1844: