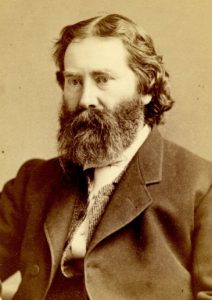

Throughout his literary career, James Russell Lowell wore many hats, from son of Cambridge and Fireside Poet to author, essayist, critic, editor, diplomat, and abolitionist. Although prolific with word usage and selected as Class Poet by the Harvard class of 1838, Lowell was suspended from attending pre-graduation festivities due to truancy and delinquency. During this period of exile from the Cambridge campus, the 19-year-old stayed with Reverend Barzallai Frost (1804-1858) in Concord, Massachusetts, where the young man met Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) and Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862). While Lowell held more conservative views than the Transcendentalists did, he wrote to friends about the Concord men with a mix of respect, fondness, aloofness, and mockery.

Lowell contributed to several literary journals, including The Boston Miscellany of Literature and Fashion (1842-1843) and Transcendentalist publications The Dial (1840-1844) and The Harbinger (1845-1849). As a poet, Lowell attempted to rival the poetry of European Romanticism through an American perspective. In 1843, he founded The Pioneer with Robert Carter (1819-1879); the magazine only published three issues. The magazine’s inaugural issue included the first publication of Edgar Allan Poe’s (1809-1849) “The Tell-Tale Heart” (1843). Various reasons given for the short-lived publication of The Pioneer include an eye disease that temporarily blinded Lowell, Carter’s irresponsibility in his partner’s stead, and the publisher, Leland and Whiting, cancelling the contract because the young editors did not meet contractual obligations. Within a short time, however, Lowell’s muse and wife, Maria, inspired him to continue writing.

As a linguist, Lowell explored the use of language, using wordplay and speech patterns as literary devices in poetry and prose. Lowell’s 1855 lecture at the Lowell Institute (1836- ), “The Five Indispensable Authors [Homer, Dante, Cervantes, Goethe, Shakespeare]” (1893), discusses how language changed after the introduction of the respective authors’ works. One particular area that fascinated Lowell was regional language variations, or dialect. The satirical poem written in Yankee dialect, The Biglow Papers (1846-1848), was first serialized in The Boston Courier (1824- 1871) newspaper and, later, published as a book (1848). This interest in the vernacular later led him to found The American Dialect Society (1889- ), an organization that dedicates itself to the study of English in North America.

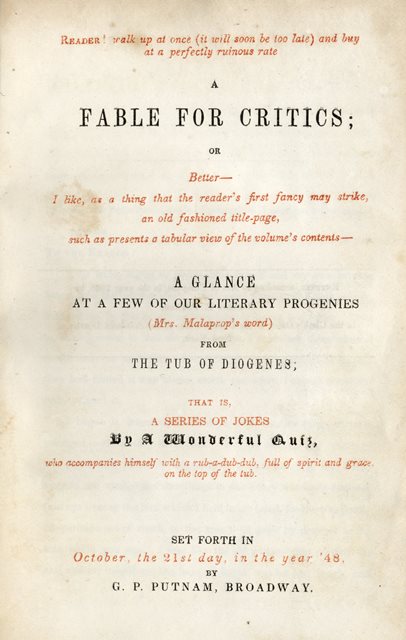

Lowell also published in 1848 A Fable for Critics, his book-length poem utilizing his vast vocabulary and wry sense of humor to satirize the Transcendentalists.

Lowell’s satirization of Thoreau from A Fable for Critics:

There comes ——, for instance; to see him’s rare sport,

Tread in Emerson’s tracks with legs painfully short;

How he jumps, how he strains, and gets red in the face,

To keep step with the mystagogue’s natural pace!

He follows as close as a stick to a rocket,

His fingers exploring the prophet’s each pocket.

Fie, for shame, brother bard; with good fruit of your own,

Can’t you let neighbor Emerson’s orchards alone?

Besides, ’tis no use, you’ll not find e’en a core, —

—— has picked up all the windfalls before.

They might strip every tree, and E. never would catch ’em,

His Hesperides have no rude dragon to watch ’em;

When they send him a dish-ful, and ask him to try ’em,

He never suspects how the sly rogues came by ’em;

He wonders why ’tis there are none such his trees on,

And thinks ’em the best he has tasted this season.

In addition to humorous portrayals of people, the poet expressed a preference for citations of other literary and historical figures, often quoting John Milton (1608- 1674) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Literary Essays IV (1890) Lowell’s essays on Alexander Pope (1688- 1744), Milton, Edmund Spenser (c. 1552- 1599), Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), and William Wordsworth (1770-1850), further explores linguistics in the works of these historical literary men. Based on Lowell’s essays and lectures, it appears the poet’s idea of originality included mentioning other poets and authors, sprinkling names throughout a work like raindrops in a passing shower.

The late-1840s and early-1850s brought a mix of misery and success to the satirist. With the deaths of three of his four young children between 1847 and 1852, followed by the loss of his wife Maria in 1853, Lowell all but stopped writing poetry. Elected to succeed Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) as chair of belles-lettres at Harvard, the essayist became a professor. Over the next five years, Lowell married his surviving daughter’s nanny and was appointed as the first editor of The Atlantic Monthly (1857- ), a position he held for 4 years.

In January 1858, at Lowell’s request, Thoreau submitted “Chesuncook,” an account of the 1853 trip to Maine, for publication in three installments. Because the editor of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science, and Art (1853-1857) modified “An Excursion to Canada” (1853) and Cape Cod (1855) without permission, Thoreau requested pre-publication proofs of the essay. When the proof sheets arrived after the second request, the author found Lowell had removed a sentence against Thoreau’s wishes in spite of his “stet” notation, an indication to ignore edits. Lowell used blue pencil to strike through the second sentence of the passage, “It is the living spirit of the tree, not its spirit of turpentine, with which I sympathize, and which heals my cuts. It is as immortal as I am, and perchance will go to as high a heaven, there to tower above me still.” Offended and furious, Thoreau sent a letter on 22 June 1858 to the editor, chastising Lowell and requesting a note about the omission in a future issue.

When I received the proof of that portion of my story printed in the July number of your magazine, I was surprised to find that the sentence — “It is as immortal as I am, and perchance will go to as high a heaven, there to tower above me still .” — (which comes directly after the words “heals my cuts,” page 230, tenth line from the top,) have been crossed out, and it occurred to me that, after all, it was of some consequence that I should see the proofs; supposing, of course, that my “Stet” &c in the margin would be respected, as I perceive that it was in other cases of comparatively little importance to me. However, I have just noticed that that sentence was, in a very mean and cowardly manner, omitted. I hardly need to say that this is a liberty which I will not permit to be taken with my MS. The editor has, in this case, no more right to omit a sentiment than to insert one, or put words into my mouth. I do not ask anybody to adopt my opinions, but I do expect that when they ask for them to print, they will print them, or obtain my consent to their alteration or omission. I should not read many books if I thought that they had been thus expurgated. I feel this treatment to be an insult, though not intended as such, for it is to presume that I can be hired to suppress my opinions.

I do not mean to charge you with this omission, for I cannot believe that you knew anything about it, but there must be a responsible editor somewhere, and you, to whom I entrusted my MS. are the only party that I know in this matter. I therefore write to ask if you sanction this omission, and if there are any other sentiments to be omitted in the remainder of my article. If you do not sanction it — or whether you do or not — will you do me the justice to print that sentence, as an omitted one, indicating its place, in the August number?

I am not willing to be associated in any way, unnecessarily, with parties who will confess themselves so bigoted & timid as this implies. I could excuse a man who was afraid of an uplifted fist, but if one habitually manifests fear at the utterance of a sincere thought, I must think that his life is a kind of nightmare continued into broad daylight. It is hard to conceive of one so completely derivative. Is this the avowed character of the Atlantic Monthly? I should like an early reply.

Yrs truly,

Henry D. Thoreau

Within a few months, the author sent two notes requesting the overdue payment of $198 for the essay. Because there is no evidence of additional correspondence between the two men, it is assumed the author was paid. Thoreau refused to provide another submission for the remainder of Lowell’s editorship.

With the publication of Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849), Lowell wrote an 11-page review in The Massachusetts Quarterly Review (1847-1850). Although in some respects the reviewer indicates an admiration for Thoreau’s observations and reflections on nature, at the same time Lowell’s disdain for the Concord surveyor is clear:

He is both wise man and poet. A graduate of Cambridge – the fields and woods, the axe, the hoe, and the rake have since admitted him ad eundem. Mark how his imaginative sympathy goes beneath the crust, deeper down than that of Burns, and needs no plough to turn up the object of its muse . . . The great charm of Mr. Thoreau’s book seems to be, that its being a book at all is a happy fortuity.

This review added to the animosity between the two men, a simmering dislike that continued the remainder of their lives. In Lowell’s My Study Windows (1871), a collection of essays that includes pieces on Thoreau and Emerson, the poet’s high regard for the Great Orator and derision of the Concord surveyor is once again expressed. Lowell viewed Thoreau as a conceited, unoriginal, and humorless, imitator of Emerson. He concluded his essay on Thoreau by saying:

He squatted on another man’s land; he borrows an axe; his boards, his nails, his bricks, his mortar, his books, his lamp, his fish-hooks, his plough, his hoe, all turn state’s evidence against him as an accomplice in the sin of that artificial civilization which rendered it possible that such a person as Henry D. Thoreau should exist at all. Magnis tamen excidit ausis. His aim was a noble and a useful one, in the direction of “plain living and high thinking.” It was a practical sermon on Emerson’s text that “things are in the saddle and ride mankind,” an attempt to solve Carlyle’s problem (condensed from Johnson) of “lessening your denominator.” His whole life was a rebuke of the waste and aimlessness of our American luxury, which is an abject enslavement to tawdry upholstery. He had “fine translunary things” in him. His better style as a writer is in keeping with the simplicity and purity of his life. We have said that his range was narrow, but to be a master is to be a master. He had caught his English at its living source, among the poets and prose-writers of its best days; his literature was extensive and recondite; his quotations are always nuggets of the purest ore: there are sentences of his as perfect as anything in the language, and thoughts as clearly crystallized; his metaphors and images are always fresh from the soil; he had watched Nature like a detective who is to go upon the stand; as we read him, it seems as if all-out-of-doors had kept a diary and become its own Montaigne; we look at the landscape as in a Claude Lorraine glass; compared with his, all other books of similar aim, even White’s “Selborne,” seem dry as a country clergyman’s meteorological journal in an old almanac. He belongs with Donne and Browne and Novalis; if not with the originally creative men, with the scarcely smaller class who are peculiar, and whose leaves shed their invisible thought-seed like ferns.

Lowell died 12 August 1891 and was interred at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA.