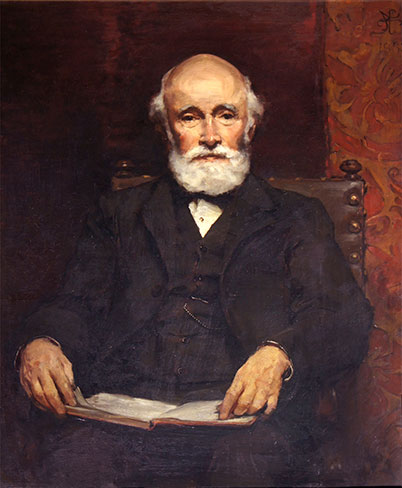

Before writing an early pre-publication review of Thoreau’s Walden (1854), and despite being considered a minor Transcendentalist figure, John Sullivan Dwight made some significant contributions to the social and literary aspects of this American movement. Closely associated with a number of Transcendentalists, Dwight was at the first meeting of “Hedge’s Club” with Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), Christopher Pearse Cranch (1813-1890), and Theodore Parker (1810-1860) in 1836. After graduating from Harvard in 1832, and Harvard Divinity School in 1836, Dwight also founded the Harvard Musical Association in 1837, remaining connected to the organization for the rest of his life. Introduced to the poetry of Lord Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892) by Emerson, Dwight wrote the first American review of Tennyson’s poetry in The Christian Examiner and General Review (1813-1869), a Unitarian publication, in 1838. Dwight penned one of the four music articles featured in The Dial (1840-1844) and worked on expanding subscriptions from the Boston and Concord area to Greenfield and Northampton, Massachusetts (MA). Ordained as a Unitarian minister in Northampton, in 1840, Dwight left the ministry when the writer joined his mentor and Emerson’s cousin, George Ripley (1802-1880) at the Utopian community, Brook Farm, around 1841.

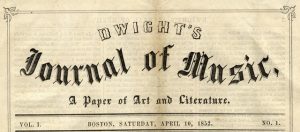

In addition to teaching Latin and music at Brook Farm, Dwight continued writing, often literary or music criticisms he published in The Harbinger (1844-1849), a Brook Farm publication, and The Pioneer (1843), edited by James Russell Lowell (1819-1891). Brook Farm was a commune of Associationism, an offshoot of Transcendentalism, which focused less on individual connections to the world and more on the community relationships. While at Brook Farm, Dwight met Mary Bullard (d. 1860) whom he married in 1851. Although Dwight played flute and taught music lessons at Brook Farm, the importance of his work in advancing standards of excellence in music criticism cannot be overlooked. As America’s first music critic and editor of the first substantial music journal, Dwight’s Journal of Music, A Paper of Art and Literature (1852–1881), Dwight set the standard by which music critics wrote in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Dwight’s Journal of Music included music and literary criticism, including book reviews, performance advertisements, poetry, and reprinted Emerson and Lowell’s speeches and lectures. Among the contributors were Cranch, Lowell, and Alexander Wheelock Thayer (1817-1897) who wrote the first scholarly biography of Dwight’s favorite composer, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827). In the August 12, 1854, edition of Dwight’s Journal of Music, Dwight composed the first review of Thoreau’s Walden. James T. Fields (1817-1881), a partner at Ticknor & Co., gave a pre-publication copy of the book for Dwight to read while on vacation in the New Hampshire mountains (see full text below).

Perhaps the appropriate setting contributed to the appeal of Walden, as Dwight writes Thoreau “is one of the few who really thinks and acts and tries life for himself, honestly weighing and reporting thereof, and in his own way (which he cares not should be others’ ways) enjoying.” Although friends with Emerson, Amos Bronson Alcott (1799-1888), Oliver Wendell Holmes (1841-1935) and other well-known Transcendentalists, there is no indication that Dwight and Thoreau met. Over the next 39 years, Dwight remained active in the music scene, participating through spectatorship, writing criticism, and documenting the developing musical styles of 19th century America.

John Sullivan Dwight died 5 September 1893 and is buried in Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, MA.

The full text of Dwight’s pre-publication review of Thoreau’s Walden, or Life in the Woods, as it appeared in Dwight’s Journal of Music, vol. V., No. 19:

For indoor reading, in the interims of physical fatigue and the lull of social excitement, say, for a few minutes after the evening company have dispersed and left us to our thoughts which will not sleep without some soothing efficacy of thoughts printed and impersonal, we have another book : — kindly placed in our hands upon the eve of starting on our journey, and with a delicate instinct of what was fitting, by our friend Fields, the poet partner in the firm of Ticknor and Co., the publishers, — a copy in advance of publication. In such hours one retires from Nature only to live her over in dreams and by whatever rush-light of his own reflections; and for such hours no truer friend and text book have we ever found than this wonderful new book called Walden, or Life in the Woods, by Henry D. Thoreau, the young Concord hermit, as he has sometimes been called. Thoreau is one of those men who has put such a determined trust in the simple dictates of common sense, as to earn the vulgar title of “transcendentalist” from his sophisticated neighbors. He is one of the few who really thinks and acts and tries life for himself, honestly weighing and reporting thereof, and in his own way (which he cares not should be others’ ways) enjoying. Of course, they find him strange, fantastical, a humorist, a theorist, a dreamer. It may be or may not. One thing is certain, that his humor has led him into a life experiment, and that into a literary report or book, that is full of information, full of wisdom, full of wholesome, bracing moral atmosphere, full of beauty, poetry and entertainment for all who have the power to relish a good book. He built himself a house in the woods by Walden pond, in Concord, where he lived alone for more than two years, thinking it false economy to eat so that life must be spent in procuring what to eat, but cultivating sober, simple, philosophic habits, and daily studying the lesson which nature and the soul of nature are perpetually teaching to the individual soul, would that but listen. Every chapter of the book is redolent of pine and hemlock. With a keen eye and love for nature, many are the rare and curious facts which he reports for us. He has become the confidant of all plants and animals, and writes the poem of their lives for us. Read that chapter upon sounds, that of the owl, the bull-frog, or that in which he commemorates the battle of the red and black ants, “red-republicans and black imperialists” which “took place in the Presidency of Polk, five years before the passage of Webster’s Fugitive Slave Bill.” Truer touches of humor and quaint, genuine, first-hand observation you will seldom find. And then his vegetable planting — read how he was “determined to know beans” And his shrewd criticisms, from his woodland seclusion, upon his village neighbors and upon “civilized life generally, in which men are slaves to their own thrift, are worthy of a philosophic, though by no means a “melancholy, Jaques.” It is the most thoroughly original book that has been produced these many days. Its literary style is admirably clear and terse and elegant; the pictures wonderfully graphic; for the writer is a poet and a scholar as well as a tough wrestler with the first economical problems of nature, and a winner of good cheer and of free glorious leisure out of what men call the “hard realities” of life. Walden pond, a half mile in diameter, in Concord town, becomes henceforth as classical as any lake of Windermere. And we doubt not, men are beginning to look to transcendentalists for the soberest reports of good hard common-sense, as well as for the models of the clearest writing.

A Selected John Sullivan Dwight Bibliography

The Dial (1840-1844)

- “Sweet is the Pleasure” (July 1840) p. 22

- “The Concerts of the Past Winter” (July 1840) p. 124

- “The Religion of Beauty” (July 1840) – a revised sermon p. 17

- “Ideals of Every-day Life,” (Jan. / April 1841) – a sermon split in two parts. Part I: I.3 p. 307; Part II: I.4, p. 446

The Pioneer, a Literary and Critical Magazine (1843), published by James Russell Lowell and R. Carter:

- “To a Pine Tree”

- “Si Descendero in Infernum, Ades”

The Harbinger (1845-1849):

- Dwight was responsible for 110 essays, critiques, and reviews, including literary criticism, book reviews, and music criticism. The Harbinger was the first American journal to publish a consistent body of music criticism.

Æsthetic Papers (1849):

Dwight’s Journal of Music, A Paper of Art and Literature (1852-1881)

Translations:

- Select Minor Poems of Goethe and Schiller (1839)

- “Confirmation of the Doctrine of Association, Drawn from the Holy Evangelists” (1845)

- Cosmogony (vol. 2)

- Le Nouveau Monde Industriel

- Dwight also translated the Christmas carol “O Holy Night” into English from French in 1855.