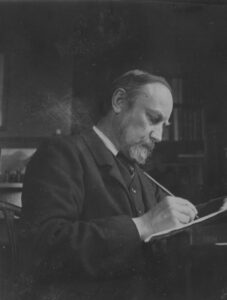

Among the descriptive titles bestowed upon Henry S. Salt are: author, editor, essayist, humanitarian and social reformer, socialist, amateur botanist, pacifist, literary critic, biographer, classical scholar, and naturalist. Yet this Englishman born in India on Sept. 20, 1851, was more than all of those. He was a biographer, husband, vegetarian, influencer, and Thoreauvian scholar.

Within a few years of his first introduction to Thoreau’s works, the Eton graduate began living a more simplified life. By 1884, he fired his staff, sold his property, and moved to a small cottage where he focused on writing and championing humanitarian causes, including class struggles and animal rights. The social reformer understood the economic climate required that “luxury on the part of one man would involve drudgery on the part of another” and sought to change the trajectory. He began writing for Justice, the journal of the Social Democratic Federation, and working as a literary critic for other socialist journals.

A prolific author, Salt wrote or edited 54 books, including 3 compilations of Thoreau’s writings, and more than 200 essays, poems, songs, and plays. Among the Thoreau works is Anti-Slavery and Reform Papers (1890), which contained “Civil Disobedience” and influenced Mohandas Gandhi’s approach to non-violent protest.

Salt’s first essay on Thoreau, published in Justice on Nov. 14, 1885, opens with, “Among those American writers who have denounced the anomalies and tyranny of Transatlantic government and society none have done so more eloquently than Henry Thoreau,” showing that he clearly identifies with ideas put forth in Walden (1854). The Cambridge alum continues, “Though not a professed Socialist, but appealing rather to the individual capabilities of man, Thoreau deserves to be attentively studied by every social reformer . . .”

Noting the lack of a thorough memoir of Thoreau, in a Nov. 1886 Temple Bar essay, “Henry D. Thoreau,” Salt laments:

“One of the causes that have contributed to the general lack of interest in Thoreau’s writings is the want of a good memoir of his life. Emerson’s account of him is excellent as far as it goes, but it is very short and cursory; while the other lives, though each is not without some merit of its own, are hardly satisfactory enough to become really popular . . .”

Over the following four years, through correspondence with Thoreau’s friends and acquaintances, Salt developed the first British biography of the author of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849). Reading as if he found a kindred spirit, the Englishman’s Life of Henry David Thoreau (1890) widened Thoreau’s audience. Furthermore, Salt believed in principles founded upon logic combined with a unifying ideal of humanity, what he called The Creed of Kinship. Lauding Thoreau’s observations and writing style, he says:

“He has been well called by Ellery Channing the ‘Poet-Naturalist;’ for to the ordinary qualifications of the naturalist—patience, watchfulness, and precision—he added in a rare degree the genius and inspiration of the poet . . . He had all that amazing knowledge of the country, its Fauna and Flora, which characterized Gilbert White, his familiarity with every bird, beast, insect, fish, reptile, and plant, being something little less than miraculous to the ordinary unobservant townsman. . .”

A founding member of the Humanitarian League in 1891, Salt helped craft a manifesto that asserted “that much good will be done by the mere placing on record of a systematic and consistent protest against the numerous barbarisms of civilisation—the cruelties inflicted by men, in the name of law, authority, and traditional habit, and the still more atrocious treatment of the lower animals, for the purpose of ‘sport’, ‘science’, ‘fashion’, and the gratification of an appetite for unnatural food . . .”

Believing people “must recognize the common bond of humanity that unites all living beings in one universal brotherhood,” including animals, Salt is considered the “Father of animal rights.” As one of the first writers arguing specifically in favor of animal rights, in his Animals’ Rights: Considered in Relation to Social Progress (1892), the humanitarian states, “The emancipation of men from cruelty and injustice will bring with it, in due course, the emancipation of animals also, the two reforms are inseparable, and neither can be fully realised alone.” More than advocating for improvements to animal welfare and being against experimenting on animals, Salt was a vegetarian. His book, A Plea for Vegetarianism (1886) guided Gandhi’s own dietary path. At the 20 Nov. 1931 meeting of the Vegetarian Society, the Indian social activist honored the Englishman by saying, he “showed me why it was a moral duty incumbent upon vegetarians not to live upon fellow-animals.”

Like Thoreau, Salt was concerned about humanity, all forms of life, social reform and justice, and land conservation. In fact, Salt’s On Cambrian and Cumbrian Hills (1908) expresses concerns about the British countryside being commercially vandalized and focuses on land protection, conservation, and stewardship.

Salt and his works became invaluable resources for American Thoreauvians. From 1929-1938, Thoreauvian scholar Raymond Adams corresponded with Salt, who kindly sent his Thoreau collection to Adams. Salt’s collection includes, but is not limited to, an 1830 essay by Thoreau, as well as Salt’s bibliography notes and correspondence from Thoreau’s friends H.G.O. Blake, George William Curtis, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Daniel Ricketson, and Franklin B. Sanborn. In addition to remembrances of the Walden author, some also shared letters from Thoreau with Salt, which are in the Raymond Adams Collection in The Thoreau Society Collections at the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods.

Salt suffered a stroke in 1933 and died at Brighton Municipal Hospital on 19 April 1939. He was cremated at Brighton Crematorium.

——————————

Selected Works by Henry Salt

-

Essays

- “Henry D. Thoreau.” (Justice, no. 96, 14 Nov. 1885)

- “Henry D. Thoreau.” (Temple Bar, vol. 78, no. 312, Nov. 1886)

- “Henry D. Thoreau.” (The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, vol. 45, no. 1, Jan. 1887)

- “Edgar Allan Poe’s Writings.” (Progress, July 1887)

- “Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Romances.” (Progress, Sept. 1887)

- “Herman Melville” (The Scottish Art Review, Nov. 1889)

- “John Burroughs’ Essays.” (The Gentleman’s Magazine, 1889)

- “Thoreau’s Poetry,” (Art Review (London), vol. 1, May 1890)

- “Thoreau’s Anti-Slavery and Reform Papers.” (Lippincott’s Magazine (English edition), Aug. 1890)

- “Marquesan Melville.” (The Gentleman’s Magazine, March 1892)

- “Memoir of Herman Melville.” (In Typee by Herman Melville (J Murray, London), 1893)

- “Thoreau” (Inquirer (London), 18 July 1896)

- “Thoreau Illustrated.” (The Saturday Review, vol. 86, 5 Nov. 1898)

- “Froude to Thoreau.” (The Academy, March 1899)

- “Henry David Thoreau: and The Humane Study of Natural History.” (The Humane Review (London), Oct. 1903)

- “Thoreau and Walt Whitman.” (Manchester Guardian, 6 Oct. 1905)

- “Thoreau and the Simple Life.” (The Humane Review (London), vol. 7, Oct. 1907)

- “More Light on Thoreau.” (The Bookman, July 1907)

- “Thoreau in Twenty Volumes.” (Fortnightly Review, vol. 83, June 1908)

- “The Widening Influence of Thoreau.” (Current Literature, June 1908)

- “David Thoreau: A Centenary Essay.” (The Humanitarian, Jan.-April 1917)

- “Thoreau as Pioneer.” (The Humanitarian, vo. 8, Sept. 1917)

- “Henry David Thoreau.” (The Vegetarian Messenger, Oct. 1932)

- “Thoreau.” (The Vegetarian Messenger and Health Review, Oct. 1937)

- A Plea for Vegetarianism (1886)

- Literary Sketches (1888)

- Flesh or Fruit? An Essay on Food Reform (1888)

- Life of Henry David Thoreau (1890)

- Animals’ Rights Considered in Relation to Social Progress (1892)

- Selections from Thoreau (1895)

- The Logic of Vegetarianism: Essays and Dialogues (1899)

- On Cambrian and Cumbrian Hills (1908)

- The Call of the Wildflower (1922)

- The Story of My Cousins (1923)

- Our Vanishing Wildflowers (1928)

- The Heart of Socialism (1928)

- Company I Have Kept (1930)

- Cum Grano, Verses and Epigrams (1931)

- The Creed of Kinship (1935) (pdf here)

Books