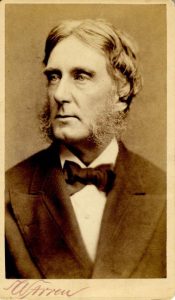

George William Curtis (24 February 1824 – 31 August 1892)

Abolitionist, writer, editor, orator

Born in Providence, Rhode Island, and educated in Jamaica Plain, Mass. before moving to New York, George William Curtis and his older brother Burrill moved to Brook Farm in 1842 for academic purposes. It was at this West Roxbury, Mass. location where George William Curtis met Ralph Waldo Emerson and became enamored with Transcendentalism. In 1844, the Curtis brothers moved to Concord, where they endeavored to learn more from Emerson, Hawthorne, and Alcott and about agriculture. Living at the homes of Minot Pratt, Gen. John Buttrick, and Edmund Hosmer over the next two years, the younger Curtis began a friendship with Thoreau. According to Walter Harding, on 29 May 1844, Muster Day, Thoreau and the new Concord resident met and struck up a conversation.

The following May, Curtis was among the group of friends that helped build Thoreau’s Walden Pond house. Thoreau writes in the “Economy” chapter of Walden:

At length, in the beginning of May, with the help of some of my acquaintances, rather to improve so good an occasion for neighborliness than from any necessity, I set up the frame of my house. No man was ever more honored in the character of his raisers than I. They are destined, I trust, to assist at the raising of loftier structures one day.

Years later, around the time Curtis co-founded and became associate editor of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine (1853-1857), he wrote of Thoreau in Homes of American Authors (1853):

Henry’s instinct is as sure toward the facts of nature as the witch-hazel toward treasure. If every quiet country town in New England had a son who, with a lore like Selborne’s, and an eye like Buffon’s, had watched and studied its landscape and history, and then published the result, as Thoreau has done, in a book as redolent of genuine and perceptive sympathy with nature as a clover-field of honey, New England would seem as poetic and beautiful as Greece. Thoreau lives in a blackberry pasture upon a bank over Walden pond, in a little house of his own building. One pleasant summer afternoon a small party of us helped him raise it, —a bit of life as Arcadian as at Brook Farm. Elsewhere in the village he turns up arrowheads abundantly, and Hawthorne mentions that Thoreau initiated him into the mystery of finding them . . .

Later in the chapter, while briefly discussing the short-lived Monday Evening Club, Curtis refers to the 15th century French romance story Valentine and Orson, in which the latter title character was raised by bears. Curtis alludes to Thoreau’s simple approach and intimate familiarity with the woods and its inhabitants in the statement, “the inflexible Henry Thoreau, a scholastic and pastoral Orson, then living among the blackberry pastures of Walden pond . . .” and that “Orson charmed us with the secrets won from his interviews with Pan in the Walden woods . . .” (Homes of American Authors, 250-252). Thoreau’s understanding of Nature charmed the future editor and a friendship began.

While known correspondence between Curtis and Thoreau spans a mere six years, from 1852-1858, with primary subjects being Thoreau’s essays on Cape Cod and Canada, the Walden author left a lasting impression on the editor. However, in 1852, Thoreau submitted the essay “An Excursion to Canada” (later published as A Yankee in Canada) for publication at Putnam’s, where Curtis was associate editor. Unfortunately, either Curtis or G.P. Putnam deemed certain passages heretical and omitted the passages without checking with Thoreau, who withdrew the manuscript after 3 of 5 published installments. In a letter to H.G.O. Blake, Thoreau laments:

It has come to an end at any rate, they will print no more, but return me my mss. when it is but little more than half done—as well as another I had sent them, because the editor Curtis requires the liberty to omit the heresies without consulting me . . . (The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, 295-300)

On 11 March 1853, an upset Thoreau writes to Curtis:

Mr. Curtis:

Together with the ms of my Cape Cod adventures Mr [George Palmer] Putnam sends me only the first 70 or 80 (out of 200) pages of the “Canada,” all which having been printed is of course of no use to me. He states that “the remainder of the mss. seems to have been lost at the printers’.” You will not be surprised if I wish to know if it actually is lost, and if reasonable pains have been taken to recover it. Supposing that Mr. P. may not have had an opportunity to consult you respecting its whereabouts—or have thought it of importance enough to inquire after particularly—I write again to you to whom I entrusted it to assure you that it is of more value to me than may appear.

With your leave I will improve this opportunity to acknowledge the receipt of another cheque from Mr. Putnam.

I trust that if we ever have any intercourse hereafter it may be something more cheering than this curt business kind.

Unlike a similar incident with James Russell Lowell, Thoreau and Curtis continued correspondence and the editor sought input before omitting passages from chapters of Cape Cod, thus avoiding additional conflict. More than two years after Thoreau mailed 100 pages of the Cape Cod manuscript to Curtis on 16 November 1852, some of which was published in four issues of Putnam’s in 1855, he withdrew the manuscript before the chapter “The Beach Again” was published.

Like Thoreau, Curtis spoke against slavery, including John Brown and the historic raid of Harper’s Ferry. When reporting on Curtis’s speech scheduled for December 1860, which was cancelled due to threats of rioting, The New York Times wrote when the orator spoke in Philadelphia days after the abolitionist’s 1859 execution, the subject was Brown’s merits. The Boston Daily Advertiser reported Curtis said Brown “was not buried but planted. He will spring up a hundred-fold.” As an ardent supporter and strong advocate for ending slavery, Curtis has been credited with Abraham Lincoln’s adoption of abolition as a key part of the presidential platform.

Leading up to the Civil War, the editor advocated for black soldiers to receive the same pay as white soldiers and for Robert Gould Shaw, Curtis’s brother-in-law, to lead the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first all-black regiment. In addition to anti-slavery, Curtis often spoke on Women’s Suffrage, as well as educational and civil service reform. In 1864, the New York state legislature elected Curtis to a lifetime appointment on the Board of Regents of the University of the State of New York, a pre-cursor to the New York City Board of Education.

The final known correspondence between Thoreau and Curtis was a brief letter, which discussed a poem by William Ellery Channing and a possible candidate for the 1860 presidential race. The health of both men began declining shortly thereafter.

Although Curtis was editor for Putnam’s, he was also a columnist and editor for other publications, such as The New-York Tribune, Harper’s Weekly, and Harper’s Monthly Magazine. In July 1862, Curtis memorialized Thoreau in “Editor’s Easy Chair,” a regular Harper’s Monthly column. The editor writes:

The name of Henry Thoreau is known to very few persons beyond those who personally know him; but it will be known long and well in our literature, and cannot fade from the memories of all who ever saw him. He was a plain New England man, who sighed neither for old England nor for Greece and Rome. In the woods and pastures of a region in no way remarkable for its natural beauty or for cultivation he found all the company he cared for, and believed that the birds and beasts and flowers he knew were certainly as good, and the men and women perhaps even better, than he could have found in any other place at any other time . . .

Thoreau was a Stoic, but he was in no sense a cynic. His neighbors in the village thought him odd and whimsical, but his practical skill as a surveyor and in wood-craft was known to them. No man was his enemy, and some of the best man were his fastest friends. But his life was essentially solitary and reserved. Careless of appearances in later days, when his hair and beard were long, if you had seen him in the woods you might have fancied Orson passing by; but had you stopped to talk with him, you would have felt that you had seen the shepherd of Admetus’s flock, or chatted with a wiser Jaques . . .

It was my good fortune to see him again, last November, when he came into the library of a friend to borrow a volume of Pliny’s letters. He was much wasted, and his doom was clear. But he talked in the old strain of wise gravity without either sentiment or sadness . . .

In an 1890 written interview published in “A Belated Knight Errant” (The Inlander, Feb. 1895, Vol. V, no. 5, 191, University of Michigan), Curtis tells Samuel Arthur Jones:

It always seemed to me one of the good fortunes of my life that I knew Concord when Emerson, Hawthorne and Thoreau, were citizens there, and that I personally knew them.

I sympathize fully with the regard and admiration for Thoreau, which inspire your paper, and if in personal intercourse he seemed to be, as Hawthorne said, a ‘cast iron man,’ he was after all no more rigid than the oak which holds fast by its own roots whatever betides.

One of my most vivid recollections of my life in Concord is that of an evening upon the shallow river with Thoreau in his boat. We lighted a huge fire of fat pine in an iron crate beyond the bow of the boat and drifted slowly through an illuminated circle of the ever-changing aspect of the river bed. In that house beautiful you can imagine what an interpreter he was.

George William Curtis died on 31 Aug. 1892, was survived by his wife Anna and 2 of their 3 children, and is buried in Moravian Cemetery in Staten Island, NY.

Partial List of Works

“A Song of Death” in The Dial (1843)

Nile Notes. By a Traveller (1851)

Lotus-Eating: A Summer Book (1852)

The Howadji in Syria (1852)

The Wanderer in Syria (1852)

Potiphar Papers (1853)

“Ralph Waldo Emerson” in Homes of American Authors (1853)

The Duty of the American Scholar to Politics and the Times, an Oration (1856)

Prue and I (1856)

“Biographical Sketch of The Author” in Cecil Dreeme by Theodore Winthrop (1861)

Trumps: A Novel (1862)

“Christmas” (1883, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine)

Equal Rights for Women: A Speech (1872)

The Public Duty of Educated Men (1877)

Our Best Society (1890)

Washington Irving: A Sketch (1891)

A Commemorative Address Delivered Before the Century Association (1892)

Other Essays from the Easy Chair (1893)

Orations And Addresses of George William Curtis, Vol. I, II, III (1894) Ed. Charles Eliot Norton

Literary and Social Essays (1895)

Early Letters of George Wm. Curtis to John S. Dwight: Brook Farm and Concord (1898)

Ars Recte Vivendi (1898)

Speeches of George William Curtis [and] Henry Ward Beecher (1898)