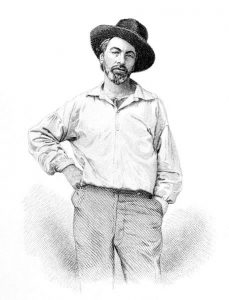

Walt Whitman (1819-1892) was greatly influenced by the work of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Whitman said, “I was simmering, simmering, simmering. Emerson brought me to a boil.” Whitman tried to fulfill the call Emerson made in such essays as “The American Scholar” and “The Poet” for a poet who would see the value of common things and be a radical departure from the conventions of the past.

Emerson, on reading the first edition of Leaves of Grass, wrote to Whitman:

I am not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of ‘LEAVES OF GRASS.’ I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed. . . It meets the demand I am always making of what seemed the sterile and stingy nature, as if too much handiwork, or too much lymph in the temperament, were making our western wits fat and mean. I give you joy of your free and brave thought. I have great joy in it. I find incomparable things said incomparably well, as they must be. I find the courage of treatment which so delights us, and which large perception only can inspire. I greet you at the beginning of a great career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere, for such a start.

Thoreau met Whitman in 1856. Thoreau and Bronson Alcott traveled to Brooklyn with the express purpose of meeting Whitman, which they did.

Whitman on Thoreau from

Horace Traubel’s With Walt Whitman in Camden

(New York: Mitchell Kennerley, 1914)

Thoreau had his own odd ways. Once he got to the house while I was out — went straight to the kitchen where my dear mother was baking some cakes — took the cakes hot from the oven. He was always doing things of the plain sort — without fuss. I liked all that about him. But Thoreau’s great fault was disdain — disdain for men (for Tom, Dick and Harry): inability to appreciate the average life even the exceptional life: it seemed to me a want of imagination. He couldn’t put his life into any other life — realize why one man was so and another man was not so: was impatient with other people on the street and so forth. We had a hot discussion about it — it was a bitter difference: it was rather a surprise to me to meet in Thoreau such a very aggravated case of superciliousness. It was egotistic — not taking that word in its worst sense…. We could not agree at all in our estimate of men — of the men we meet here, there, everywhere — the concrete man. Thoreau had an abstraction about man — a right abstraction: there we agreed. We had our quarrel only on this ground. Yet he was a man you would have to like — an interesting man, simple, conclusive…. When I lived in Brooklyn — in the suburbs — probably two miles distant from the ferries—though there were cheap cabs, I always walked to the ferry to get over to New York. Several times when Thoreau was there with me we walked together. Thoreau, in Brooklyn, that first time he came to see me, referred to my critics as ‘reprobates.’ I asked him: ‘Would you apply so severe a word to them?’ He was surprised: ‘Do you regard that as a severe word? reprobates? what they really deserve is something infinitely stronger, more caustic: I thought I was letting them off easy.’

*****

Thoreau was a surprising fellow — he is not easily grasped — is elusive: yet he is one of the native forces — stands for a fact, a movement, an upheaval: Thoreau belongs to America, to the transcendental, to the protestors: then he is an outdoor man: all outdoor men everything else being equal appeal to me. Thoreau was not so precious, tender, a personality as Emerson: but he was a force — he looms up bigger and bigger: his dying does not seem to have hurt him a bit: every year has added to his fame. One thing about Thoreau keeps him very near to me: I refer to his lawlessness — his dissent — his going his own absolute road let hell blaze all it chooses.

*****

Henry was not all for me—he had his reservations: he held back some: he accepted me—my book—as on the whole something to be reckoned with: he allowed that I was formidable: said so to me much in that way: over in Brooklyn: why, that very first visit: ‘Whitman, do you have any idea that you are rather bigger and outside the average—may perhaps have immense significance?’ That’s what he said: I did not answer. He also said: ‘There is much in you to which I cannot accommodate myself: the defect may be mine: but the objections are there.’

Thoreau on Whitman from

The Writings of Henry David Thoreau (1906)

Volume VI: Familiar Letters

Thoreau to H.G.O. Blake, 19 November 1856

He is apparently the greatest democrat the world has seen. Kings and aristocracy go by the board at once, as they have long deserved to. A remarkably strong though coarse nature, of a sweet disposition, and much prized by his friends. Though peculiar and rough in his exterior, his skin (all over (?)) red, he is essentially a gentleman. I am still somewhat in a quandary about him, — feel that he is essentially strange to me, at any rate; but I am surprised by the sight of him. He is very broad, but, as I have said, not fine. He said that I misapprehended him. I am not quite sure that I do. He told us that he loved to ride up and down Broadway all day on an omnibus, sitting beside the driver, listening to the roar of the carts, and sometimes gesticulating and declaiming Homer at the top of his voice.

Thoreau to H,G.O. Blake, 7 December 1856

That Walt Whitman, of whom I wrote to you, is the most interesting fact to me at present. I have just read his 2nd edition (which he gave me) and it has done me more good than any reading for a long time. Perhaps I remember best the poem of Walt Whitman an American & the Sun Down Poem. There are 2 or 3 pieces in the book which are disagreeable to say the least, simply sensual. He does not celebrate love at all. It is as if the beasts spoke. I think that men have not been ashamed of themselves without reason. No doubt, there have always been dens where such deeds were unblushingly recited, and it is no merit to compete with their inhabitants. But even on this side, he has spoken more truth than any American or modern that I know. I have found his poem exhilarating encouraging. As for its sensuality, — & it may turn out to be less sensual than it appeared — I do not so much wish that those parts were not written, as that men & women were so pure that they could read them without harm, that is, without understanding them. One woman told me that no woman could read it as if a man could read what a woman could not. Of course Walt Whitman can communicate to us no experience, and if we are shocked, if we are shocked, whose experience is it that we are reminded of?

On the whole it sounds to me very brave & American after whatever deductions. I do not believe that all the sermons so called that have been preached in this land put together are equal to it for preaching —

We ought to rejoice greatly in him. He occasionally suggests something a little more than human. You cant confound him with the other inhabitants of Brooklyn or New York. How they must shudder when they read him! He is awefully good.

To be sure I sometimes feel a little imposed on. By his heartiness & broad generalities he puts me into a liberal frame of mind prepared to see wonders — as it were sets me upon a hill or in the midst of a plain — stirs me well up, and then — throws in a thousand of brick. Though rude & sometimes ineffectual, it is a great primitive poem — an alarum or trumpet-note ringing through the American Camp. Wonderfully like the Orientals, too, considering that when I asked him if he had read them, he answered, “No: tell me about them.”

I did not get far in conversation with him, — two more being present, — and among the few things which I chanced to say, I remember that one was, in answer to him as representing America, that I did not think much of America or of politics, and so on, which may have been somewhat of a damper to him.

Since I have seen him, I find that I am not disturbed by any brag or egoism in his book. He may turn out the least of a braggart of all, having a better right to be confident.

He is a great fellow.

Whitman visits Concord

From Whitman’s Specimen Days (1882)

A Visit, at the last, To R.W Emerson

Concord, Mass.—Out here on a visit—elastic, mellow, Indian-summery weather. Came to-day from Boston, (a pleasant ride of 40 minutes by steam, through Somerville, Belmont, Waltham, Stony Brook, and other lively towns,) convoy’d by my friend F. B. Sanborn, and to his ample house, and the kindness and hospitality of Mrs. S. and their fine family. Am writing this under the shade of some old hickories and elms, just after 4 P. M., on the porch, within a stone’s throw of the Concord river. Off against me, across stream, on a meadow and side-hill, haymakers are gathering and wagoning-in probably their second or third crop. The spread of emerald-green and brown, the knolls, the score or two of little haycocks dotting the meadow, the loaded-up wagons, the patient horses, the slow-strong action of the men and pitch-forks—all in the just-waning afternoon, with patches of yellow sun-sheen, mottled by long shadows—a cricket shrilly chirping, herald of the dusk—a boat with two figures noiselessly gliding along the little river, passing under the stone bridge-arch—the slight settling haze of aerial moisture, the sky and the peacefulness expanding in all directions and overhead—fill and soothe me.

Same evening.—Never had I a better piece of luck befall me: a long and blessed evening with Emerson, in a way I couldn’t have wish’d better or different. For nearly two hours he has been placidly sitting where I could see his face in the best light, near me. Mrs. S.’s back-parlor well fill’d with people, neighbors, many fresh and charming faces, women, mostly young, but some old. My friend A. B. Alcott and his daughter Louisa were there early. A good deal of talk, the subject Henry Thoreau—some new glints of his life and fortunes, with letters to and from him—one of the best by Margaret Fuller, others by Horace Greeley, Channing, &c.—one from Thoreau himself, most quaint and interesting. (No doubt I seem’d very stupid to the room-full of company, taking hardly any part in the conversation; but I had “my own pail to milk in,” as the Swiss proverb puts it.) My seat and the relative arrangement were such that, without being rude, or anything of the kind, I could just look squarely at E., which I did a good part of the two hours. On entering, he had spoken very briefly and politely to several of the company, then settled himself in his chair, a trifle push’d back, and, though a listener and apparently an alert one, remain’d silent through the whole talk and discussion. A lady friend quietly took a seat next him, to give special attention. A good color in his face, eyes clear, with the well-known expression of sweetness, and the old clear-peering aspect quite the same.

Next Day.—Several hours at E.’s house, and dinner there. An old familiar house, (he has been in it thirty-five years,) with surroundings, furnishment, roominess, and plain elegance and fullness, signifying democratic ease, sufficient opulence, and an admirable old-fashioned simplicity—modern luxury, with its mere sumptuousness and affectation, either touch’d lightly upon or ignored altogether. Dinner the same. Of course the best of the occasion (Sunday, September 18, ’81) was the sight of E. himself. As just said, a healthy color in the cheeks, and good light in the eyes, cheery expression, and just the amount of talking that best suited, namely, a word or short phrase only where needed, and almost always with a smile. Besides Emerson himself, Mrs. E., with their daughter Ellen, the son Edward and his wife, with my friend F. S. and Mrs. S., and others, relatives and intimates. Mrs. Emerson, resuming the subject of the evening before, (I sat next to her,) gave me further and fuller information about Thoreau, who, years ago, during Mr. E.’s absence in Europe, had lived for some time in the family, by invitation.

Other Concord Notations

Though the evening at Mr. and Mrs. Sanborn’s, and the memorable family dinner at Mr. and Mrs. Emerson’s, have most pleasantly and permanently fill’d my memory, I must not slight other notations of Concord. I went to the old Manse, walk’d through the ancient garden, enter’d the rooms, noted the quaintness, the unkempt grass and bushes, the little panes in the windows, the low ceilings, the spicy smell, the creepers embowering the light. Went to the Concord battle ground, which is close by, scann’d French’s statue, “the Minute Man,” read Emerson’s poetic inscription on the base, linger’d a long while on the bridge, and stopp’d by the grave of the unnamed British soldiers buried there the day after the fight in April ’75. Then riding on, (thanks to my friend Miss M. and her spirited white ponies, she driving them,) a half hour at Hawthorne’s and Thoreau’s graves. I got out and went up of course on foot, and stood a long while and ponder’d. They lie close together in a pleasant wooded spot well up the cemetery hill, “Sleepy Hollow.” The flat surface of the first was densely cover’d by myrtle, with a border of arbor-vitæ, and the other had a brown headstone, moderately elaborate, with inscriptions. By Henry’s side lies his brother John, of whom much was expected, but he died young. Then to Walden pond, that beautifully embower’d sheet of water, and spent over an hour there. On the spot in the woods where Thoreau had his solitary house is now quite a cairn of stones, to mark the place; I too carried one and deposited on the heap. As we drove back, saw the “School of Philosophy,” but it was shut up, and I would not have it open’d for me. Near by stopp’d at the house of W. T. Harris, the Hegelian, who came out, and we had a pleasant chat while I sat in the wagon. I shall not soon forget those Concord drives, and especially that charming Sunday forenoon one with my friend Miss M., and the white ponies.

Boston Common—More of Emerson

Oct. 10–13.—I spend a good deal of time on the Common, these delicious days and nights—every mid-day from 11.30 to about 1—and almost every sunset another hour. I know all the big trees, especially the old elms along Tremont and Beacon streets, and have come to a sociable-silent understanding with most of them, in the sunlit air, (yet crispy-cool enough,) as I saunter along the wide unpaved walks. Up and down this breadth by Beacon street, between these same old elms, I walk’d for two hours, of a bright sharp February mid-day twenty-one years ago, with Emerson, then in his prime, keen, physically and morally magnetic, arm’d at every point, and when he chose, wielding the emotional just as well as the intellectual. During those two hours he was the talker and I the listener. It was an argument-statement, reconnoitring, review, attack, and pressing home, (like an army corps in order, artillery, cavalry, infantry,) of all that could be said against that part (and a main part) in the construction of my poems, “Children of Adam.” More precious than gold to me that dissertation—it afforded me, ever after, this strange and paradoxical lesson; each point of E.’s statement was unanswerable, no judge’s charge ever more complete or convincing, I could never hear the points better put—and then I felt down in my soul the clear and unmistakable conviction to disobey all, and pursue my own way. “What have you to say then to such things?” said E., pausing in conclusion. “Only that while I can’t answer them at all, I feel more settled than ever to adhere to my own theory, and exemplify it,” was my candid response. Whereupon we went and had a good dinner at the American House. And thenceforward I never waver’d or was touch’d with qualms, (as I confess I had been two or three times before)