To the last number of the third volume of “The Dial” Lydia Maria Child contributed an article on “What is Beauty?” It appeared under her own name. which was then well known to the reading public. From this brief paper it is evident that Mrs. Child was a transcendentalist. although we know from other of information that she did not closely affiliate herself with the members of that school She was in large degree an eclectic or an independent, studying all creeds sympathetically. and yet accepting none without reserve. Her position was well defined by Wendell Phillips when he said of her that “in her many-sidedness she did not merely bear with other creeds; she heartily sympathized with all forms of religious belief. pagan. classic. oriental, and Christian. All she asked was that they should be real.”

This catholicity of spirit was admirably shown in her book, published in 1855, on “The The Progress of Religious Ideas through Successive Ages.” She wrote to a friend while it was in preparation: “I am going to tell the plain, unvarnished truth, as nearly as I can understand it, and let Christians and Infidels. Orthodox and Unitarians, Catholics and Protestants and Swedenborgians, growl as they like. They all will growl if they notice the book at all; for each one will want to have his own theory favored, and the only thing I have conscientiously aimed at is not to favor any theory.” At about the time “The Dial” was publishing Mrs. Child was much interested in the teachings of Swedenborg. and she was inclined to join the New Church. In a letter to Ellis Gray Loring, May 27, 1841, she speaks of this desire, but says she is withheld from its gratification because the New Church is opposed to reforms. “Let me go where I will, it keeps an outward hold upon me, more or less weak on one side, while reforms grapple me closely on the other. I feel that they are opposite, nay, discordant. My affections and imagination cling to one with a love that will not be divorced; my reason and conscience keep fast hold of the other, and will not be loosened. What shall I do? The temptation is to quit reforms, but that is of the devil; for there is clearly more work for me to do in that field. I suppose I must go on casting a loving, longing look toward the star-keeping clouds of mysticism, which look down s0 mysterious and still into my heart.”

In 1840, while living in Northampton, Mrs. Child had listened to the preaching of John S. Dwight, and she had found much satisfaction in it. “He has ministered to my soul,” she wrote to a friend, “in seasons of great need. I think that was all he was sent here for, and that the parish are paying for a missionary to me.” At a later time she was drawn to the teachings of Theodore Parker, and after reading his biography by John Weiss, she wrote that it had confirmed her impression that he “was the greatest man, morally and intellectually that our country has ever produced.” One of the most practical of busy women, devoting her whole life to loving service for others, she had a tendency towards mysticism, a love for what transcendentalism connotes. Writing to her brother, in 1838, she said that the Unitarian “looks upward for the coming dawn and calls it transcendentalism.”

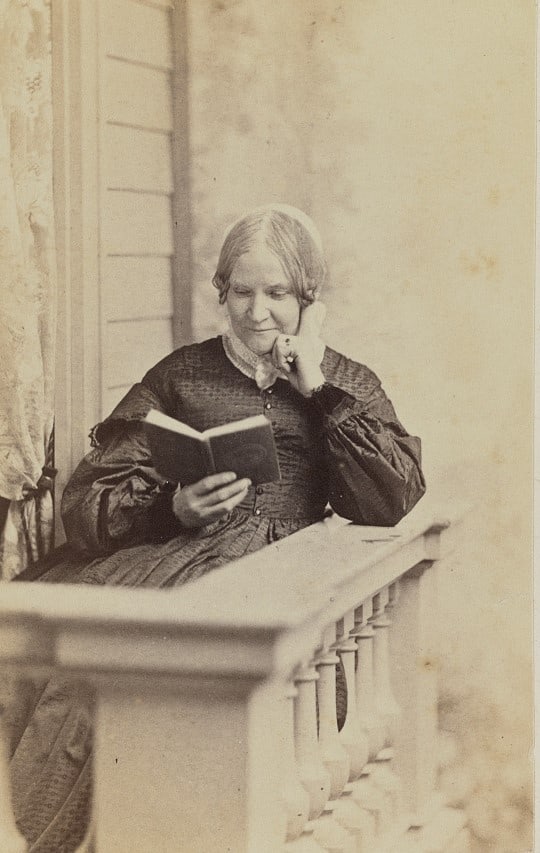

Lydia Maria Child was born in Medford, Mass., February 11, 1802. She was educated in the public schools and in a private seminary of her native town. She owed much to her brother, Convers Francis, a Unitarian minister, and for many years a professor in the Harvard Divinity School. The reading of “Waverley” led her to try her own hand at fiction, with the result that she published “Hobomok,” a story of early New England life, at the age of twenty-one. Other novels followed, as well as books for children. In 1826 she began the publication of “The Juvenile Miscellany,” the first magazine for children published in the country. She soon became widely known, and her writings were very popular. In 1833, however, she published “An Appeal in behalf of that Class of Americans called Africans,” and she was at once regarded as a fanatic, and lost most of her popularity. Mrs. Child devoted herself to three lines of reformatory work, that of aiding women in their efforts for educational and professional advancement being the first. She was the first American woman to secure for herself a prominent and national recognition as an author. Her series called ” The Ladies’ Family Library,” including a “History of the Condition of Women,” expressed this phase of her work.

The devotion of Mrs. Child to the cause of human freedom was unfailing and heroic. “It is no exaggeration to say,” wrote Whittier in the biographical sketch he prepared to accompany a volume of her letters, “that no man or woman at that period rendered more substantial service to the cause of freedom, or made such a renunciation in doing it.” She sacrificed much for this cause, of personal friendships, of literary success, and of financial reward. After the “Appeal” she wrote an “Anti-Slavery Catechism,” 1836; “The Evils of Slavery,” and the “Curse of Slavery,” 1836; “Philothea: a Romance,” 1836; “Authentic Narratives of American Slavery,” 1838; “Correspondence with Governor Wise,” 1860 ; “The Patriarchal Institution,” 1860 ; “The Freedman’s Book,” 1865; “A Romance of the Republic,” 1867, as well as other works, that dealt with this phase of the national life.

As already intimated, Mrs. Child was keenly interested in the problems of religion, and especially in the practical realization of the results of the motives it inculcates. She did not deal with questions of theology, but with the worldwide impulses that lead to the religious life. Her work in three volumes on the “Progress of Religious Ideas” was the earliest in this country to study religion comparatively, and while it bears no comparison with later works in the same field, it was nobly planned and executed. It showed the depth and catholicity of her religious convictions, and that she wrote to further a more unsectarian and spiritual interpretation of the higher phases of life. In two other books, “Looking towards Sunset,” and “Aspirations of the World,” she also indicated her faith and her tolerant spirit.

Lydia Francis married David Lee Child, a Boston lawyer, in 1828. For a time she was editor of “The Anti-Slavery Standard” in New York, and while there she wrote for the “Boston Joumal” letters that were widely read and copied. Two volumes of these were published as “Letters from New York,” 1843 and 1845. She lived in the family of Isaac Hopper, a well-known member of the Friends’ society, who was a zealous anti-slavery worker and philanthropist, and she wrote a biography of him. In 1854 she went with her husband to the town of Wayland, where the remainder of her life was spent. In a lonely neighborhood, at some distance from the nearest village, she lived in a most simple way. She cheerfully accepted a life of poverty in order that she might give liberally to the persons and the reforms she loved. The most rigid economy enabled her to devote, in spite of her poverty, considerable sums to helping others. She sincerely and nobly exemplified the altruistic spirit, thinking not of herself, but always remembering to minister to those she thought deserving.

—George Willis Cooke, A Historical

and Biographical Introduction to the Dial

(Cleveland: Rowfant Club, 1902) v. 2, pp. 166-169