In 1821, Henry David Thoreau’s uncle, Charles Dunbar (1780-1856), partnered with Cyrus Stow (1787-1876) in a Bristol, NH, plumbago mining and pencil-manufacturing company named Dunbar & Stow. Plumbago, a type of carbon also called graphite or black lead, is one ingredient used for pencil cores. By 1823, the partnership dissolved and Dunbar went into business with his brother-in-law, John Thoreau, Sr. (1787-1859), renaming the business John Thoreau & Co.

Shortly after renaming the company, the Oct. 1824 issue of New England Farmer reported that, at the 1823 Massachusetts Agricultural Society exhibition in Brighton, MA, Chairman Richard Sullivan and committee awarded $5 to John Thoreau & Co. “for a specimen of excellent Lead Pencils, manufactured of Plumbago, a native of this country.” The following year, Chairman John Buttrick awarded $2 to the Concord pencil-maker “for a specimen of excellent Lead Pencils, Manufactured from American Plumbago.” The Massachusetts Agricultural Repository and Journal (1825) reported, “the Lead Pencils exhibited by J. Thorough [sic] & Co. were superior to any specimens exhibited in past years.”

By 1829, their pencil manufacturing moved to Concord, MA, producing high enough quality to be sold in Boston. At the time, most American made pencils were dusty, smudgy without necessarily being equally hard, and frequently brittle, throughout the industry. However, Henry David Thoreau researched European pencil-making processes and reverse engineered a better blend of graphite and clay in 1843.

In Henry David Thoreau as Remembered by a Young Friend (1917), Edward Waldo Emerson, son of Sage of the Concord, recalls:

“. . . it appears they invented a process, very simple, but which at once put their black lead for fineness at the head of all manufactured in America. This was simply to have the narrow churn-like chamber around the mill-stones prolonged some seven feet high, opening into a broad, close, flat box, a sort of shelf. Only lead-dust that was fine enough to rise to that height, carried by an upward draught of air, and lodge in the box was used, and the rest ground over. . .”

This refining process created a better pencil with less dust and harder lead, which means less inadvertent smudges for artists, with a less brittle core for reduced breakage and lower need to sharpen. Some Boston art teachers insisted their students only used Thoreau pencils, unrivaled at the time for high quality American pencils.

Further refining of the process came after Henry David’s 1846 trip to Maine. He wrote in his Journal, “I observed here pencils which are made in a bungling way by grooving a round piece of cedar then putting in the lead and filling up the cavity with a strip of wood.” Thoreau then designed a machine to drill a length-wise hole in the wood slats, thus eliminating the need to glue two slats together, making a more efficient manufacturing process, and chose not to patent either process.

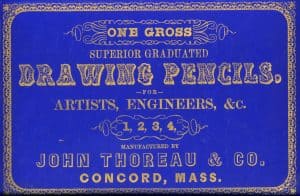

John Thoreau & Co. was the first American pencil manufacturer to market pencils using a standard of hardness, graded 1-4 and in terms of the letters S for soft and H for hard. Now, there are 19 grades of pencil hardness: 14B, 12B, 10B, 8B, 7B, 6B, 5B, 4B, 3B, 2B, B, HB, F, H, 2H, 3H, 4H, 5H, and 6H. The best known is the HB, also called the number 2 or 2HB, pencil. A higher number means a harder graphite core, while the letters H and B mean hard or black and F indicates sharpening to a fine point. More graphite and less clay means a lighter pencil mark and less frequent sharpening. Thoreau pencils sold by the gross for 75 cents per dozen, considered expensive at the time. For those that could afford these pencils, the cost could be justified by the higher quality.

The deep blue boxes with gold lettering state:

J.T. & CO.Invite ARTISTS AND CONNOISSEURS, who are particular in the choice of a Pencil, to compare theirs to others in the market, feeling confident that they will be found equal to any, whether of domestic or foreign manufacture, in all the qualities which constitute a GOOD PENCIL.

Additional text on sales display boxes claimed Thoreau pencils were “free from inequalities and grit” and “would not be affected by changes in temperature.”

Eventually, as electrotyping became more used, the sale of refined plumbago was more lucrative. Pencil-making and the turn to plumbago sales allowed the family to buy a house, pay for Henry David Thoreau’s Harvard education, and live a comfortable middle-class life. The enterprising young man attempted selling pencils to pay for publication of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849), though he took a loss on the endeavor. By 1853, the Thoreau pencil factory stopped making pencils.