In 1846, Henry David Thoreau spent a night in the Concord jail after deciding not to pay his poll tax. This tax was collected from every adult, regardless of income. Thoreau had not paid the annual poll tax for six years in protest against Massachusetts’ support of slavery and the Mexican War. Drawing from his time in jail, Thoreau called on the public not “to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right” in his essay “Civil Disobedience.” This essay was first published in 1849 under the title “Resistance to Civil Government” in Elizabeth Peabody’s Æsthetic Papers.

Before Thoreau’s famous call to action in “Civil Disobedience,” and even before Thoreau was arrested, there were at least two other men in Concord who chose not to pay the poll tax.

For it matters not how small the beginning may seem to be: what is once well done is done forever. (Civil Disobedience, 370)

Perhaps the first Concord man who got in trouble for not paying the poll tax was Brister Freeman. Freeman had been enslaved in Concord by Timothy Wesson and then John Cuming. He gained his freedom after serving in the American Revolution. Once free, Brister Freeman pooled his resources with another former slave, Charlestown Edes, to purchase land in Walden Woods in 1785. Exactly like Thoreau, Freeman did not pay his poll tax for six years. His debt accumulated to 7 pounds, 19 shillings. Town officials gave Freeman the choice to sign over his property or spend time in debtor’s prison. Freeman, who did odd jobs to provide for his family, decided to surrender his half of the property. On January 17, 1791, Freeman signed over his property to the town.

A strange detail is that John Cuming had left money to the town of Concord to pay any debts that Brister Freeman might accumulate. The town used that money to pay Brister Freeman’s poll tax. But Freeman still had to sign over his land. The town did not ask Brister Freeman to vacate the property he lived on. It is believed that the town made Freeman sign over his property so that he could not participate in town meeting, which was granted to all property owners.

Thoreau might not have been aware of the details of Freeman’s problems with the poll tax, but he was aware of the result. On his 1857 survey of Walden Woods, Thoreau noted that the “Brister Lot” had become “the state’s because the owner, Brister was a foreigner.”

How does it become a man to behave toward this American government to-day? I answer, that he cannot without disgrace be associated with it. I cannot for an instant recognize that political organization as my government which is the slave’s government also. (Civil Disobedience, 360)

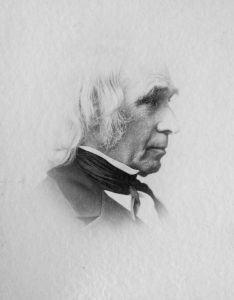

Fifty years after Brister Freeman signed over his land, in 1843, Thoreau’s friend Amos Bronson Alcott did not pay the Concord poll tax. A few months before he moved to his utopian experiment Fruitlands, Alcott was arrested for not paying the poll tax. He was arrested, but he did not spend time behind bars. When Alcott was taken to the jailhouse, the jailer wasn’t there. As the constable looked for him, Alcott waited. After two hours, Samuel Hoar, a local attorney, heard about the arrest and paid the poll tax on behalf of Alcott. Bronson Alcott had wanted to be jailed, much like Thoreau would be three years later, as a form of protest. Working with even less than the single night Thoreau spend in jail, Alcott’s friend from England, Charles Lane, wrote a series of letters for The Liberator arguing against “the iniquity of the incorporated state system.”

Thoreau wrote to Emerson at the time Alcott was arrested:

I suppose they have told you how near Mr. Alcott went to the jail, but I can add a good anecdote to the rest. When Staples came to collect Mrs. Ward’s taxes, my sister Helen asked him what he thought Mr. Alcott meant,—what his idea was,—and he answered, “I vum, I believe it was nothing but principle, for I never heard a man talk honester.”

Alcott and Lane’s protest against the state, in part, inspired Thoreau’s time in prison three years later.

Ultimately, Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience” essay has inspired a great number of protestors including Martin Luther King, Mohandas Gandhi, and Leo Tolstoy. Lesser known Thoreau-inspired protestors include Emma Goldman, who opposed the WWI draft in America, and the people who resisted the Nazis in Denmark.

Brister Freeman’s story also has a direct connection to present day protestors. John Cuming’s property, where Freeman spent twenty-five years enslaved, is now the location of the state prison in Concord. About a hundred years after Thoreau’s time in prison, Malcolm X learned about Thoreau from a fellow inmate in 1947 before being transferred to the Concord State Prison. Both of Brister Freeman’s and Thoreau’s lives connect to modern protestors, with the words in “Civil Disobedience” and the land of the Concord State Prison.

…But if [the law] is of such a nature that it requires you to be the agent of injustice to another, then, I say, break the law. Let your life be a counter-friction to stop the machine. (Civil Disobedience, 368)

It’s undeniable that Thoreau’s message has had a lasting effect on the world. While spreading Thoreau’s message of “Civil Disobedience,” it’s important to remember Brister Freeman and Bronson Alcott who helped set the precedent for this small beginning in Concord.