Bronson Alcott writes to his brother Junius Alcott:

Thoreau is elected curator of the Concord Lyceum (Concord Lyceum records, Special Collections, Concord Free Public Library, Concord, Mass.).

William Ellery Channing writes to Thoreau:

My dear Thoreau,

The hand-writing of your letter is so miserable, that I am not sure I have made it out. If I have it seems to me you are the same old sixpence you used to be, rather rusty, but a genuine piece.

I see nothing for you in this earth but that field which I once christened “Briars”; go out upon that, build yourself a hut, & there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive. I see no alternative, no other hope for you. Eat yourself up, you will eat nobody else, nor anything else.

Concord is just as good a place as any other; there are indeed, more people in the streets of that village, than in the streets of this. This is a singularly muddy town; muddy, solitary, & silent.

They tell us, it is March; it has been all March in this place, since I came. It is much warmer now, than it was last November, foggy, rainy, stupefactive weather indeed.

In your line, I have not done a great deal since I arrived here; I do not mean the Pencil line, but the Staten Island line, having been there once, to walk on a beach by the Telegraph, but did not visit the scene of your dominical duties, Staten Island is very distant from No. 30 Ann St.

I saw polite William Emerson in November last, but have not caught any glimpse of him since then. I am as usual offering the various alternations from agony to despair, from hope to fear, from pain to pleasure. Such wretched one-sided productions as you, know nothing of the universal man; you may think yourself well off.

That baker,—[Isaac Thomas] Hecker, who used to live on two crackers a day I have not seen, nor [Rebecca Gray?] Black, nor Vathek [John Wilhelm Vethake], nor Danedaz nor [Isaiah] Rynders, or any of Emerson’s old cronies, excepting James [Henry James, Sr.], a little fat, rosy Swedenborgian amateur, with the look of a broker, & the brains & heart of a Pascal.-Wm [William Henry] Channing I see nothing of him; he is the dupe of good feelings, & I have all-too many of these now.

I have seen something of your friends, [Giles] Waldo, and [William] Tappan, I have also seen our good man “McKean,” the keeper of that stupid place the “Mercantile Library.” I have been able to find there no book which I should like to read.

Respecting the country about this city, there is a walk at Brooklyn rather pleasing, to ascend upon the high ground & look at the distant ocean. This is a very agreeable sight. I have been four miles up the island in addition, where I saw, the bay; it looked very well, and appeared to be in good spirits.

I should be pleased to hear from Kamkatscha [i.e. Concord, Mass.] occasionally; my last advices from the Polar Bear [i.e. Ralph Waldo Emerson] are getting stale. In additions to this, I find that my corresponding members at Van Dieman’s land, [i.e. Fruitlands] have wandered into limbo. I acknowledge that I have not lately corresponded very much with that section.

I hear occasionally from the World; everything seems to be promising in that quarter, business is flourishing, & the people are in good spirits. I feel convinced that the Earth has less claims to our regard, then formerly, these mild winters deserve a severe censure. But I am well aware that the Earth will talk about the necessity of routine, taxes, &c. On the whole, it is best not to complain without necessity.

Mumbo Jumbo [Horace Greeley] is recovering from his attack of sore eyes, & will soon be out, in a pair of canvas trousers, scarlet jacket, & cocked hat. I understand he intends to demolish all the remaining species of Terichism at a meal; I think it’s probable it will vomit him. I am sorry to say, that Roly-Poly has received intelligence of the death of his only daughter, Maria; this will be a terrible wound to his paternal heart.

I saw Teufelsdrock a few days since; he is wretchedly poor, has an attack of the colic, & expects to get better immediately. He said a few words to me, about you. Says he, that fellow Thoreau might be something, if he would only take a journey through the “Everlasting No”, thence for the North Pole. By God”, said the old clothes-bag “warming up”, I should like to take that fellow out into the Everlasting No, & explode him like a bomb-shell; he would make a loud report. He needs the Blumine flower business; that would be his salvation. He is too dry, too confused, too chalky, too concrete. I want to get him into my fingers. It would be fun to see him pick himself up.” I “camped” the old fellow in a majestic style.

Does that execrable compound of sawdust & stagnation, Alcott still prose about nothing, & that nutmeg-grater of a [Edmund] Hosmer yet shriek about nothing,—does anybody still think of coming to Concord to live, I mean new people? If they do, let them beware of you philosophers.

Ever yrs my dear Thoreau,

W E C

Thoreau attends Wendell Phillips’ Concord Lyceum lecture (The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, 163-166). See entries 12 and 28 March.

Thoreau writes to the editor of The Liberator regarding Wendell Phillips’ speech of 11 March before the Concord Lyceum:

We have now, for the third winter, had our spirits refreshed, and our faith in the destiny of the Commonwealth strengthened, by the presence and the eloquence of Wendell Phillps; and we wish to tender to him our thanks our sympathy. The admission of this gentleman into the Lyceum has been strenuously opposed by a respectable portion of our fellow-citizen, who themselves, we trust, whose descendants, at least, we know, will be as faithful conserver of the true order, whenever that shall be the order of the day,—and in each instance, the people have voted that they would hear him, by coming themselves and bringing their friends to the lecture room, and being very silent that they might hear. We saw some men and women, who had long ago come out, going in once more through the free and hospitable portals of the Lyceum; and many of our neighbors confessed, that they had had a ‘sound season’ this once.

It was the speaker’s aim to show what the State and above all the Church had to do, and now, alas! Have done, with Texas and Slavery and how much, on the other hand, the individuals should have to do with Church and State. These were fair themes, and not mistimed; and his words were addressed to ‘fit audience, and not few.’

We must give Mr. Phillips the credit of being a clean, erect, and what was once called a consistent man. He at least is not responsible for slaver, nor for American Independence; for the hypocrisy and superstition of the Church, nor the timity and selfishness of the State; nor for the difference and willing ignorance of any. He stands so distinctly, so firmly, and so effectively, alone, and one honest man is so much more than a host, that we cannot but feel that we cannot but feel that he does himself injustice when he reminds us of ‘the American Society, which he represents.’ It is rare that we have the pleasure of listening to so clear and orthadox a speaker, who obviously has so few crack or flaws in his moral nature—who, having words at his command in a remarkable degree, has much more than words, if there should fail, in his unquestionable earnestness and integrity— and, aside from their admiration at his rhetoric, secures the genuine respect of his audience. He unconsciously tells his biography as he proceeds, and we see him early and earnestly deliberating on these subjects, and wisely and bravely, without counsel or consent of any, occupying a ground at first, from which the varying tides of public opinion cannot drive him.

No one could mistake the genuine modesty and truth with which he affirmed, when speaking of the framers of the Constitution,—‘I am wiser than they,’ who with him has improved these sixty years’ experience of its working; or the uncompromising consistency and frankness of the prayer which concluded, not like the Thanksgiving proclamations, with —‘God save the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,’ but God dash it into a thousand pieces, there there shall not remain a fragment on which a man can stand, and dare not to tell his name—referring to the case of Frederick—————; to our disgrace we know what to call him, unless Scotland will lend us the spoils of one of her Douglasses, out of history or fiction, for a season, till we be hospitable and brave enough to hear his proper name, a fugitive slave in one more sense than we; who has proved himself the possessor of a fair intellect, and has won a colorless reputation in these parts; and who, we trust, will be as superior to degradation from the sympathies of freedom, as from the anticipathies of Slavery. When, said Mr. Phillips, he communicated to a New-Bedford audience, the other day, his purpose of writing his life, and telling his name, and the name of his master, and the place he ran from, the murmur ran around the room, and was anxiously whispered by the sons of the Pilgrims, ‘He had better not!’ and it was echoed under the shadow of Concord monument, ‘He had better not!’

We would fain express our appreciation of the freedom and steady wisdom, so rare in the reformer, with which he declared that he was not born to abolish slavery, but to do right, We have heard a few, a very few, good political speakers, who afforded us the pleasures of great intellectual power and acuteness, of soldier-like steadiness, and of a graceful and natural oratory; but in this man the audience might detect a sort of moral principle and integrity, which was more stable than their firmness, more discriminating that his own intellect, and more graceful than his rhetoric, which was not working for temporary or trivial ends. It is so rare and encouraging to listen to an orator, who is content with another alliance than with the popular party, or even with the sympathising school of the martyrs, who can afford sometimes to be his own auditor if the mob stay away, and hears himself without reproof, that we feel ourselves in danger of slandering all mankind by affirming, that here is one, who is at the same time an eloquent speaker and a righteous man.

Perhaps, on the whole the most interesting fact elicited by these addresses, is the readiness of the people at large, of whatever sect or party, to entertain with good will and hospitality, the most revolutionary and heretical opinions, when frankly and adequately, and in some sort of cheerfully, expressed, Such clear and candid declarations of opinion served like an electuary to whet and clarify the intellect all parties and furnished each one with an additional argument for that right he asserted.

We considered Mr. Phillips one of the most conspicuous and efficient champions of a true Church and State now in the field, and would say to him, such as are like him—‘God speed you.’ If you know of any champions in the ranks of his opponents, who has the valor and courtesy even of Paynim chivalry, if not the Christian graces and refinement of this knight, you will do us a service by directing hm to these fields forthwith, where the lists are now open, and he shall be hospitably entertained. For as yet the Red-cross knight has shown us only the gallant device upon his shield, and his admirable command of his steed, prancing and curvetting in the empty lists; but we wait to see who, in the actual breaking of lances, will come tumbling upon the plain.

The letter is published on the 28th of March.

Thoreau lectures on “Concord River” at the Unitarian Church for the Concord Lyceum (Studies in the American Renaissance 1995, 146).

The Liberator publishes Thoreau’s letter of 12 March to William Lloyd Garrison, editor, commending Wendell Phillips’ lecture of 11 March at the Concord Lyceum:

Thoreau writes in Walden:

Thoreau writes in Walden:

Thoreau writes in Walden:

Thoreau writes in Walden:

Thoreau’s helpful acquaintances were Ralph Waldo Emerson, A. Bronson Alcott, William Ellery Channing, George William Curtis, Burrill Curtis, Edmund Hosmer, John Hosmer, Edmund Hosmer Jr., and Andrew Hosmer (The Days of Henry Thoreau, 181).

Daniel Waldo Stevens writes to Thoreau asking:

Nathaniel Hawthorne writes to publisher Evert Duyckinck concerning Thoreau’s ability to write a book for Duyckinck’s American book series:

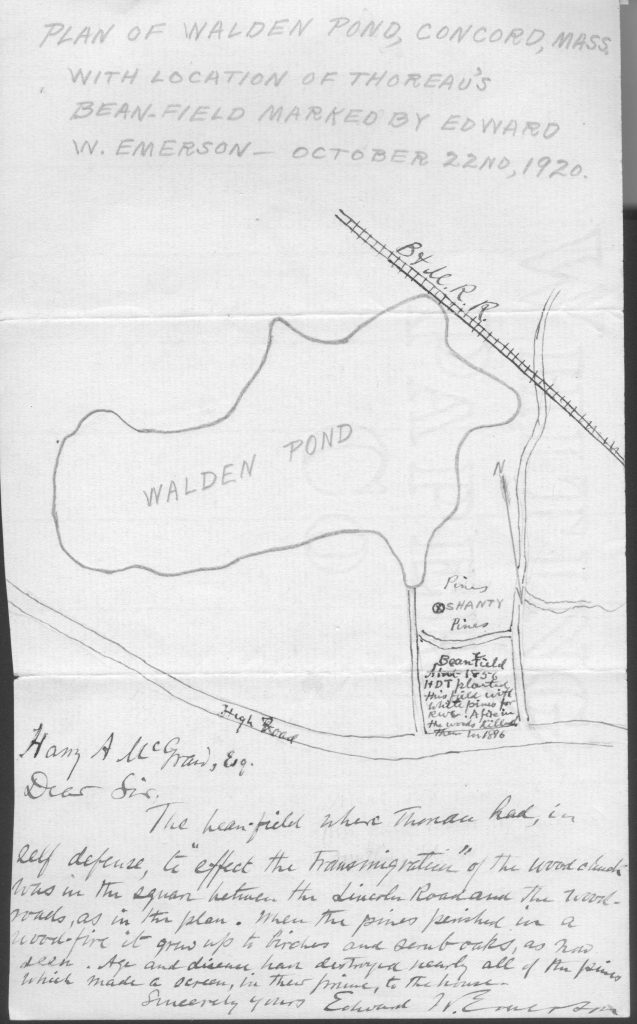

Thoreau goes to live at Walden Pond.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in Walden:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

And earlier to-day came five Lestrigones, railroad men who take care of the road, some of them at least. They still represent the bodies of men, transmitting arms and legs and bowels downward from those remote days to more remote. They have some got a rude wisdom withal, thanks to their dear experience. And one with them, a handsome younger man, a sailor-like, Greek-like man, says: “Sir, I like your notions. I think I shall live so myself. Only I should like a wilder country, where there is more game. I have been among the Indians near Appalachicola. I have lived with them. I like your kind of life. Good day. I wish you success and happiness.”

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau completes the first draft of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (Revising Mythologies, 254).

Thoreau sends Benjamin Marston Watson three boxes with a cover note:

Yrs

Henry D. Thoreau

Thoreau writes in his journal:

* By Eliot Warburton.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Joseph Hosmer recalls:

The building was not then finished, the chimney had no beginning—the sides were not battened, or the walls plastered. It stood in the open field, some thirty rods from the lake, and the “Devil’s Bar” and in full view of it.

Upon its construction he had evidently bestowed much care, and the proportions of it, together with the work, were very much better than would have been expected of a novice, and he seemed well pleased with his effort.

The entrance to the cellar was thro’ a trap door in the center of the room. The king-post was an entire tree, extending from the bottom of the cellar to the ridge-pole, upon which we descended, as the sailors do into the hold of a vessel.

His hospitality and manner of entertainment were unique, and peculiar to the time and place.

The cooking apparatus was primitive and consisted of a hole made in the earth and inlaid with stones, upon which the fire was made, after the manner at the sea-shore, when they have a clam-bake.

When sufficiently hot remove the smoking embers and place on the fish, frog, etc. Our bill of fare included roasted horn pout, com, beans, bread, salt, etc. Our viands were nature’s own, “sparkling and bright.”

I gave the bill of fare in English and Henry rendered it in French, Latin and Greek.

The beans had been previously cooked. The meal for our bread was mixed with lake water only, and when prepared it was spread upon the surface of a thin stone used for that purpose and baked . . . It was according to the old Jewish law and custom of unleavened bread, and of course it was very, very primitive.

When the bread had been sufficiently baked the stone was removed, then the fish placed over the hot stones and roasted—some in wet paper and some without—and when seasoned with salt, were delicious.

He was very much disappointed in not being able to present to me one of his little companions—a mouse.

He described it to me by saying that it had come upon his back as he leaned against the wall of the building, ran down his arm to his hand, and ate the cheese while holding it in his fingers; also, when he played upon the flute, it would come and listen from its hiding place, and remain there while he continued to play the same tune, but when he changed the tune, the little visitor would immediately disappear.

Owing perhaps to some extra noise, and a stranger present, it did not put in an appearance, and I lost that interesting part of the show—but I had enough else to remember all my life.

Thoreau writes to James Munroe & Co. on behalf of the Concord Women’s Anti-Slavery Society:

The Ladies have concluded to pay you your dues, and take the remaining addresses* at once. Your bill has been mislaid and they may be mistaken in the amount. I noticed what seemed to me one error in the false correction (in the bill) of what was apparently the original & correct charge,—adding your 4 cents per copy to the 52 which Mr Emerson took. These of course were no more than the author usually takes, and properly speaking, were not left on sale. If they are not mistaken whole amount = 16.96

False charge = 2.08

14.88 Will you adjust this, and forward the remaining copies by express.Yrs respecly

Henry D Thoreau

agent for the Society

P.S. They are willing you should keep 25 copies on the original terms.

*Ralph Waldo Emerson’s The Emancipation of the Negroes in the British West Indies. The address, which was delivered to the Concord Women’s Anti-Slavery Society, was published 9 September 1844.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

In his old house—an ‘unlucky castle now’ pervious to wind & snow—lay his old clothes his outmost cuticle curled up by habit as it were like himself upon his raised plank bed. One black chicken still goes to roost lonely in the next apartment—stepping silent over the floor—frightened by the sound of its own wings—never-croaking—black as night and silent too, awaiting reynard—its God actually dead.

And in his garden never to be harvested where corn and beans and potatoes had grown tardily unwillingly as if foreknowing that the planter would die—how how luxurious the weeds—cockles and burs stick to your clothes, and beans are hard to find—corn never got its first hoeing.

Walden Pond. Thoreau harvests beans and potatoes for a profit of $8.71½ after expenses (Walden, 60-61).

Ralph Waldo Emerson writes to Thoreau:

Dear Sir,

Mrs Brown [Lucy Jackson Brown] wishes very much to see you at her house tomorrow (Saturday) Evening to meet Mr Alcott. If you have any leisure for the useful arts, L. E. [Lidian Emerson] is very desirous of your aid. Do not come at any risk of the Fine.

R. W. E.

Ralph Waldo Emerson writes to Thoreau:

Can you not without injurious delay to the shingling give a quarter or a half hour tomorrow morning to the direction of the Carpenter who builds Mrs [Lucy Jackson] Brown’s fence? [Isaac] Cutler has sent another man, & will not be here to repeat what you told him so that the new man wants new order. I suppose he will be on the ground at 7, or a little after & Lidian shall keep your breakfast warm.

But do not come to the spoiling of your day.

R. W. E.

Ralph Waldo Emerson pays Thoreau $5 for building a fence (Ralph Waldo Emerson journals and notebooks. Houghton Library, Harvard University).

Ralph Waldo Emerson loans Thoreau $7 (Ralph Waldo Emerson journals and notebooks. Houghton Library, Harvard University).

Thoreau writes in Walden:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Left house on account of plastering, Wednesday, November 12th, at night; returned Saturday, December 6th (Journal, 1:387).

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau issues the following receipt to Sally Pierce Hosmer:

To surveying wood-lot, and making a plan of the same.

——$2.50

Recd — Payt

Henry D Thoreau

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal: