Thoreau writes an essay on Charles Milton’s poems “L’Allegro” and “Il Penseroso” (Early Essays and Miscellanies, 73-78; MS, Abernethy Collection of American Literature. Middlebury College Special Collections, Middlebury, Vt.).

Thoreau checks out The works of the English poets, from Chaucer to Cowper, volume 3 edited by Alexander Chalmers and Essays on the formation and publication of opinions, and on other subjects by Samuel Bailey from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau checks out Adventures on the Columbia river, including the narrative of a residence of six years on the western side of the Rocky mountains among various tribes of Indians hitherto unknown by Ross Cox from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau writes an untitled (and apparently unassigned) essay on “madness” (Early Essays and Miscellanies, 79; The Transcendentalists and Minerva, 1:183).

Thoreau checks out Journal of a voyage up the river Missouri, performed in eighteen hundred eleven by Henry Marie Brackenridge from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288; The Transcendentalists and Minerva, 1:184).

Thoreau checks out Terra australis cognita, volume 1 by Charles de Brosses from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau submits an essay on the “Characteristics of the Speeches of the Devils in Paradise Lost, Book II,” for a class assignment given him on 16 December 1836 (Thoreau’s Harvard Years, part 2:12; The Transcendentalists and Minerva, 1:184; Early Essays and Miscellanies, 79-83).

Thoreau checks out The Roman history, from the foundation of the city of Rome, to the destruction of the Western empire, volume 2 by Oliver Goldsmith from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau checks out Gentleman’s Magazine, volume 5 from Harvard Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau checks out The poetical works of John Milton, volume 5 from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau checks out The prose works of John Milton, volume 7 from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau submits an essay on the prompt “Speak of the characteristics which, whether humorously or reproachfully, we are in the habit of ascribing to the people of different sections of our own country,” for an assignment given him on 3 February (Thoreau’s Harvard Years, part 2:13; Early Essays and Miscellanies, 83-86; MS, Abernethy Collection of American Literature. Middlebury College Special Collections, Middlebury, Vt.).

Thoreau checks out Ornithological biography, or An account of the birds of the United States of America, volumes 1–3 by John James Audubon from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau submits a college essay on the prompt “Compare some of the Methods of gaining or exercising public Influence: as, Lectures, the Pulpit, Associations, the Press, Political Office,” for a class assignment given him on 17 February (Thoreau’s Harvard Years, part 2:13; Early Essays and Miscellanies, 86-88; MS, Abernethy Collection of American Literature. Middlebury College Special Collections, Middlebury, Vt.).

Thoreau checks out Specimens of the British poets, with biographical and critical notices and an essay on English poetry, volume 1 by Thomas Campbell from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau checks out The history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire, volume 1 by Edward Gibbon, The Italian sketchbook by Henry Theodore Tuckerman, and Reliques of ancient English poetry, volume 2 edited by Thomas Percy from the library of the Institute of 1770.

Thoreau also checks out The works of the English poets, from Chaucer to Cowper, volume 1 edited by Alexander Chalmers from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau submits an essay on the prompt “Name, and speak of Titles of Books, either as pertinent to the matter, or merely ingenious and attractive,” for a class assignment given him on 3 March (Thoreau’s Harvard Years, part 2:13; Early Essays and Miscellanies, 88-93).

Thoreau finishes his second term of his senior year. He earns 650 points to give him a cumulative total of 12,112 and ranking him twenty-third in his class of forty-four students. He also starts his final term at Harvard with the following classes:

- Intellectual Philosophy taught by Francis Bowen; reading A treatise on political economy by Jean Baptiste Say and Commentaries on the constitution of the United States by Joseph Story

- Natural History taught by Thaddeus William Harris; reading The philosophy of natural history by William Smellie

- English with bi-weekly themes and monthly forensics taught by Edward T. Channing

- German taught by Hermann Bokum

- Spanish taught by Francis Sales

- Lectures on German and Northern Literature with Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

- Lectures on Mineralogy with John White Webster

- Lectures on Anatomy with John C. Warren

- Lectures on Natural History (Zoology and Botany) with Thaddeus William Harris

Thoreau checks out an unidentified item recorded as “Book of Shipwrecks” from the library of the Institute of 1770 (The Transcendentalists and Minerva, 1:86).

Thoreau also checks out Lectures on the English poets by William Hazlitt and Philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful by Edmund Burke from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau checks out Letters on demonology and witchcraft by Sir Walter Scott from the library of the Institute of 1770 (The Transcendentalists and Minerva, 1:86).

Thoreau also checks out Poems on several occasions: and two critical essays by Samuel Say and Lives of the most eminent English poets, volume 1 by Samuel Johnson from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau submits an essay on the prompt “‘The Thunder’s roar, the Lightning’s flash, the billows’ roar, the earthquake’s shock, all derive their dread sublimity from death.’ The Inheritance, ch. 56. Examine this theory,” for a class assignment given him on 17 March (Thoreau’s Harvard Years, part 2:13; Early Essays and Miscellanies, 93-99).

Thoreau checks out Nature by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship. Trans. by Thomas Carlyle by Johann Goethe and renews The history of the decline and fall of the Roman empire, volume 1 by Edward Gibbon from the library of the Institute of 1770.

Thoreau checks out Narrative of the Arctic land expedition to the mouth of the Great Fish River and along the shores of the Arctic Ocean, in the years 1833, 1834, and 1835 by Sir George Back and Poems of Mr. Gray; To which are added memoirs of his life and writings, volumes 1-4 by Thomas Gray from Harvard College Library.

Thoreau checks out The works of John Milton, historical, political, and miscellaneous, volume 1 and De la religion, considérée dans sa source, ses formes et ses développements, volume 1 by Henri Benjamin Constant de Rebecque from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau writes an essay on “the opinions of Dymond and Mrs. Opie respecting the general obligation to tell the truth; are they sound and applicable? Vide Dymond’s ‘Essays on Morality’ and Mrs. Opie’s ‘Illustrations of Lying’” (Early Essays and Miscellanies, 99-101; MS, Albert Edgar Lownes collection on Henry David Thoreau, John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, R.I.).

Thaddeus William Harris and Henry David Thoreau, along with some other friends, found Harvard’s Natural History Society

Thoreau checks out a book by Robert Burns from the library of the Institute of 1770, though the title is unidentified. At the time, the library held Works in 3 volumes, The life of Robert Burns, and Poems (The Transcendentalists and Minerva, 1:86).

Thoreau submits an essay on the prompt “Paley in his Natural Theology, chap. 23, speaks of minds utterly averse to ‘the flatness of being content with common reasons’—and considers the highest minds ‘most liable to this repugnancy.’ See the passage, and explain the moral or intellectual defect,” for a class assignment given him on 31 March.

Thoreau checks out An introduction to physiological and systematical botany by Sir James Edward Smith from Harvard College University (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau submits an essay on the prompt “‘The clock sends me to bed at ten, & makes me rise at eight. I go to bed awake, and arise asleep; but I have ever held conformity one of the best arts of life, and though I might choose my own hours, I think it proper to follow theirs.’ E. Montague’s Letters. Speak of the duty, inconvenience and dangers of conformity, in little things and great,” for a class assignment given him on 5 May.

Thoreau checks out Robin Hood: A collection of all the ancient poems, songs, and ballads, volume 1 by Joseph Ritson from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau writes an essay on the prompt “Whether Moral Excellence tend directly to increase Intellectual Power?” (Early Essays and Miscellanies, 106-108; MS, Abernethy collection of American Literature. Middlebury College Special Collections, Middlebury, Vt.).

Thoreau writes an autobiography for his class book (Early Essays and Miscellanies, 113-115; MS, pp. 105 and 106, Harvard University Archives, Cambridge, Mass.).

Thoreau checks out De la religion, considérée dans sa source, ses formes et ses développements, volumes 2 and 3 by Henri Benjamin Constant de Rebecque from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau writes an essay on the prompt “The mark or standard by which a nation is judged to be barbarous or civilized. Barbarities of civilized states,” for a class assignment given him on 19 May (Thoreau’s Harvard Years, part 2:13; Early Essays and Miscellanies, 108-111; MS, Abernethy collection of American Literature. Middlebury College Special Collections, Middlebury, Vt.).

Thoreau earns $25 from the exhibition money granted to Seniors (Thoreau’s Harvard Years, part 1:19).

Thoreau checks out Illustrations of Anglo-Saxon poetry by John Josias Conybeare and Elements of Anglo-Saxon grammar by Joseph Bosworth from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau gives a farewell gift of a first edition of Nature by Ralph Waldo Emerson to William Allen and inscribes it:

D. H. Thoreau

A something to have sent you,

Tho’ it should serve nae other end,

Than just a kind memento!

But how the subject-theme may gang

Ane hardly can determine;

I’m sure its not an empty sang,

Nor yet is it a sermon.”

Thoreau also checks out Introduction to the history of philosophy by Victor Cousin and John Milton: his life and times, religious and political opinions by Joseph Ivimey from the library of the Institute of 1770, and renews Nature by Ralph Waldo Emerson, which he checked out on 3 April.

Josiah Quincy, president of Harvard University, writes to Ralph Waldo Emerson:

Your view concerning Thoreau is entirely in consent with that which I entertain. His general conduct has been satisfactory and I am willing and desirous that whatever falling off there had been in his scholarship should be attributable to his sickness. He had, however, imbibed some notions concerning emulation & college rank, which had a natural tendency to diminish his zeal, if not his exertion. His instructors were impressed with the conviction that he was indifferent, even to a degree that was faulty and that they could not recommend him consistent with the rule, by which they are usually governed in relation to beneficiaries. I have, always, entertained a respect for, and interests in him, and was willing to attribute any apparent neglect, or indifference to his ill health rather than to wilfulness. I obtained from the instructors the authority to state all the facts to the Corporation, and submit the result to their discretion. This I did, and that body granted twenty-five dollars, which was within ten, or at most fifteen dollars of any sum, he would have received had no objection been made. There is no doubt that, from some cause, an unfavorable opinion has been entertained, since his return after his sickness, of his disposition to exert himself. To what it has been owing may be doubtful. I appreciate very fully the goodness of his heart and the strictness of his moral principle; and have done as much for him as, under the circumstances, was possible.

Very respectfully, your humble servant,

Josiah Quincy

Thoreau checks out Chronicle of Scottish poetry; from the 13th century to the union of the crowns, volume 2 by James Sibbald and Vitæ excellentium imperatorium: cum versione Anglicâ by Cornelius Nepos from Harvard College Library (Companion to Thoreau’s Correspondence, 288).

Thoreau writes an essay on Titus Pomponius Atticus:

Truth is what whole of which Virtue, Justice, Benevolence and the like are the parts, the manifestations; she includes and runs through them all. She is continually revealing herself. Why, then, be satisfied with the mere reflection of her genial warmth and light? why dote upon her faint and fleeting echo, if we can bask in her sunshine, and hearken to her revelations when we will? No man is so situated that he may not, if he choose, find her out; and when he has discovered her, he may without fear go all lengths with her; but if he take her at second hand, it must be done cautiously; else she will not be pure and unmixed.

Wherever she manifests herself, whether in God, in man, or in nature, by herself considered, she is equally admirable, equally inviting; though to our view she seems, from her relations, now stern and repulsive, now mild and persuasive. We will then consider Truth by herself, so that we may the more heartily adore her, and more confidently follow her.

Next, how far was the life of Atticus a manifestation of Truth? According to Nepos, his Latin biographer: “He so carried himself as to seem level with the lowest, and yet equal to the highest. He never sued for any preferment in the State, because it was not to be obtained by fair and honorable means. He never went to law about anything. He never altered his manner of life, though his estate was greatly increased. His compliance was not a strict regard to truth.”

Truth neither exalteth nor humbleth herself. She is not too high for the low, nor yet too low for the high. She never stoops to what is mean or dishonorable. She is persuasive, not litigious, leaving Conscience to decide. Circumstances do not affect her. She never sacrificeth her dignity that she may secure for herself a favorable reception. Thus far the example of Atticus may safely be followed. But we are told, on the other hand: “That, finding it impossible to live suitably to his dignity at Rome, without offending one party or the other, he withdrew to Athens. That he left Italy that he might not bear arms against Sylla. That he so managed by taking no active part, as to secure the good will of both Cæsar and Pompey. Finally, that he was careful to avoid even the appearance of crime.”

It is not a characteristic of Truth to use men tenderly, nor is she over-anxious about appearances. The honest man, according to George Herbert,-is

To God, his neighbor and himself most true;

Whom neither fear nor fawning can

Unpin, or wrench from giving all their due.

Who rides his sure and even trot,

While the World now rides by, now lags behind.

Who, when great trials come,

Nor seeks nor shuns them, but doth always stay

Till he the thing, and the example weigh;

All being brought into a sum,

What place or person calls for, he doth pay.”

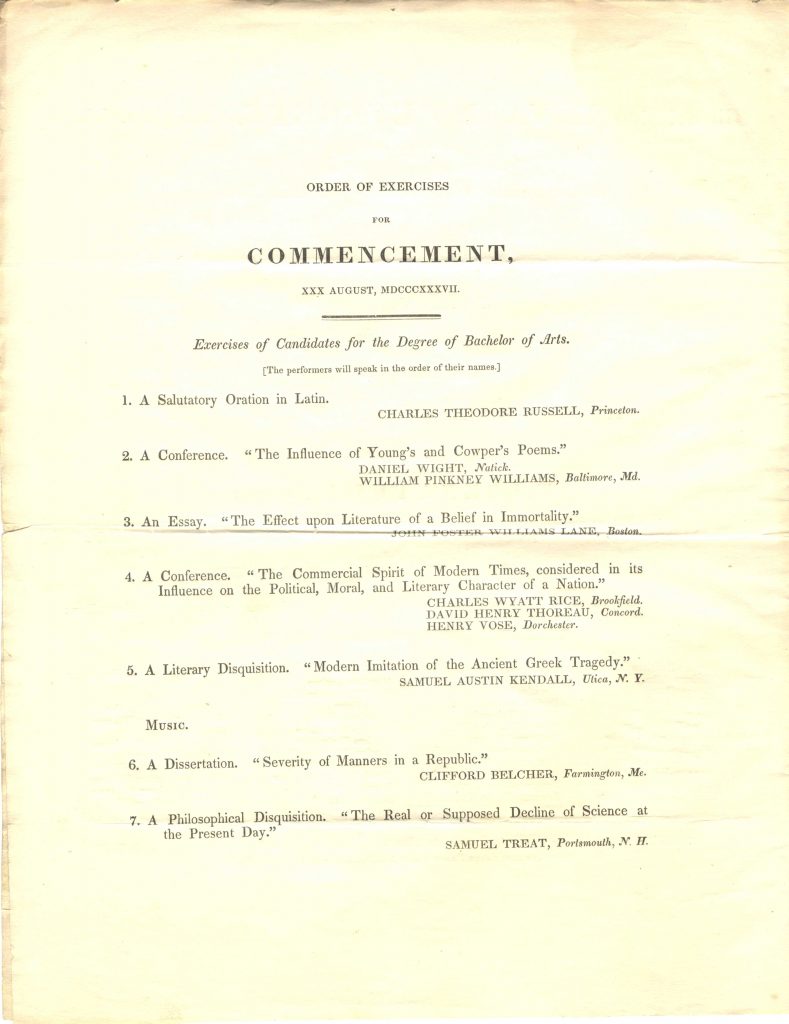

Thoreau completes his senior year with a final ranking of nineteenth in a class of forty-four students. With a grand total of 14,397 points, he qualifies for a part in the Commencement Exercises on 30 August (Thoreau’s Harvard Years, part 1:18).

Thoreau probably attends the dedication of the monument commemorating the battle of 19 April 1775 (The Days of Henry Thoreau, 48). John Shepard Keyes recalls the day:

Thoreau performs a mathematical proof:

This will be manifest if the student but attends to the manner of forming a series of power or a retrograde order. If, for instance, in the series a0, a1, a2, a3, a4, a5, a6, we commence with a6, we may obtain the preceding term, either by dividing by a, or by diminishing the exponent by unity. Thus, if we divide aaaaaa by a, we shall have aaaaa. If we prefer to diminish the exponent by unity, we shall have a5. Now we may, in the same manner, make our series extend to powers having negative exponents, i.e. either by dividing always the preceding term by a, or by diminishing its exponent by unity. If we divide by a, commencing with a0 or 1, we obtain 1/a, or 1/a1 and so on. If we diminish the exponent of the same term by unity, we shall have a-1. Hence a-1=1/a.

1/a=a0/ai now as we divide by subtracting one exponent from the other, we have a0/a1=a-1.

Thoreau checks out The works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke from the library of the Institute of 1770 (The Transcendentalists and Minerva, 1:86).

Thoreau also inscribes Charles Theodore Russell’s class book with his poem, “I love a careless streamlet” (Emerson Society Quarterly 7 (2nd quarter 1957):2):

Ubique.

I love a careless streamlet,

That takes a mad-clap leap,

And like a sparkling beamlet

Goes dashing down the steep.

—–

Like torrents of the mountain

We’ve coursed along the lea,

From many a crystal fountain

Toward the far-distant sea.

And now we’ve gained life’s valley,

And through the lowlands roam,

No longer may’st thou dally,

No longer spout and foam.

May pleasant meads await thee,

Where thou may’st freely roll

Towards that bright heavenly sea,

Thy resting place and goal.

And when thou reach’st life’s down-hill,

So gentle be thy stream,

As would not turn a grist-mill

Without the aid of steam.

Thoreau checks out Letters, conversations, & recollections of S. T. Coleridge, volumes 1 and 2, Memorials of Mrs. Hemans, with illustrations of her literary character from her private correspondence, volumes 1 and 2 by Henry Fothergill Chorley, Library of the old English prose writers, volume 2 edited by Alexander Young, and either Goetz of Berlichingen, with the iron hand by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe or Dramatic works by John Ford (it’s unclear from the record which is referred to) from the library of the Institute of 1770, and renews Introduction to history of philosophy by Victor Cousin, which he checked out on 25 June.

Thoreau and Charles Stearns Wheeler live in a hut by Flints Pond that Wheeler had previously built. They spend their time reading and recuperating at the hut, but take their dinners at the Wheelers (The Days of Henry Thoreau, 49).

Harvard’s Class of 1837 holds its (apparently raucous) Valedictory Exercises, or Class Day. It’s not certain whether Thoreau attended (The Days of Henry Thoreau, 49; Emerson Society Quarterly 7 (2nd quarter 1957):2).

John Shepard Keyes recalls spending several days with Thoreau in Stoughton Hall at Harvard University:

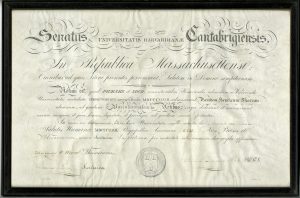

Thoreau graduates from Harvard University.

Thoreau participates as one of the speakers of a conference on “The Commercial Spirit of Modern Times, Considered in its influence on the Political, Moral, and Literary Character of a Nation”:

Indeed, could one examine this beehive of ours from an observatory among the stars, he would perceive an unwonted degree of bustle in these later ages. There would be hammering and chipping, baking and brewing, in one quarter; buying and selling, money-changing and speech-making, in another. What impression would he receive form so general and impartial a survey? Would it appear to him that mankind used this world as not abusing it? Doubtless he would first be struck with the profuse beauty of our orb; he would never tire of admiring its varied zones and seasons, with their changes of livery. He could not but notice that restless animal for whose sake it was contrived, but where he found one to admire with him his fair dwelling place, the ninety and nine would be scraping together a little of the gilded dust upon its surface.

In considering the influence of the commercial spirit on the moral character of a nation, we have only to look at its ruling principle. We are to look chiefly for its origin, and the power that still cherishes and sustains it, in a blind and unmanly love of wealth. And it is seriously asked, whether the prevalence of such a spirit can be prejudicial to a community? Wherever it exists it is too sure to become the ruling spirit, and as a natural consequence, it infuses into all our thoughts and affections a degree of its own selfishness; we become selfish in our patriotism, selfish in our domestic relations, selfish in our religion.

Let men, true to their natures, cultivate the moral affections, lead manly and independent lives; let them make riches the means and not the end of existence, and we shall hear no more of the commercial spirit. The sea will not stagnate, the earth will be as green as ever, and the air as pure. This curious world which we inhabit is more wonderful than it is convenient, more beautiful than it is useful—it is more to be admired and enjoyed then, than used. The order of things should be somewhat reversed,—the seventh should be man’s day of toil, wherein to earn his living by the sweat of his brow, and the other six his sabbath of the affections and the soul, in which to range this wide-spread garden, and drink in the soft influences and sublime revelations of Nature.

But the veriest slave of avarice, the most devoted and selfish worshipper of Mammon, is toiling and calculating to some other purpose than the mere acquisition of the good things of this world; he is preparing, gradually and unconsciously it may be, to lead a more intellectual and spiritual life. Man cannot if he will, however degraded or sensual his existence, escape Truth. She makes herself to be heard above the din and bustle of commerce, by the merchant at his desk, or the miser counting his gains, as well as in the retirement of the study, by her humble and patient follower.

Our subject has its bright as well as its dark side. The spirit we are considering is not altogether and without exception bad. We rejoice in it as one more indication of the entire and universal freedom which characterizes the age in which we live—as an indication that the human race is making one more advance in that infinite series of progressions which awaits it. We rejoice that the history of our epoch will not be a barren chapter in the annals of the world,—that the progress which it shall record bids fair to be general and decided. We glory in those very excesses which are a source of anxiety to the wise and good, as an evidence that man will not always be the slave of matter, but erelong, casting off those earth-born desires which identify him with the brute, shall pass the days of his sojourn in this his nether paradise as becomes the Lord of Creation.

“Hard times came to the court in 1837. They were not the new president’s fault, but Van Buren inherited the blame for them nevertheless. People wanted a scapegoat, perhaps, and in Van Buren they soon found one. State Street, the Boston financial section, was hard hit.

Newly graduated from Harvard, Thoreau looked for a job and started a journal. The first item still preserved is short. “ ‘What are you doing now?’ he asked. ‘Do you keep a journal?’ So I make my first entry to-day.” Thoreau was already looking for solitude and the opportunity to live his own life. The panic of 1837 find no place in his journal. Thoreau camped by Flint’s Pond for some weeks with his Harvard friend Sterns Wheeler, thus anticipating the Walden experiment.”

Thoreau teaches at the Concord Center School for about two weeks, but resigns abruptly when Deacon Nehemiah Ball orders corporal punishment as a means to quiet an unruly class. The incident is recalled by several sources:

I didn’t understand the reason for this then, but I found out later. It seems he’d been taken to task by someone—I think it was Deacon Ball—for not using the rod enough. So Thoreau thought he’d give the other way a thorough trial, and he did, for one day. The next day he said he wouldn’t keep the school any longer, if that was the way he had to do it.

When I went to my seat, I was so mad that I said to myself: “When I’m grown up, I’ll whip you for this, old feller.” But . . . I never saw the day I wanted to do it.—why Henry Thoreau was the kindest hearted of men.

The incident is also alluded to in an annual school committee report, published the following year:

Prudence Ward writes to her sister Caroline Ward Sewall on 25 September:

James Richardson Jr. writes to Thoreau:

After you had finished your part in the Performances of Commencement, (the tone and sentiment of which by the way I liked much, as being of a sound philosophy,) I hardly saw you again at all. Neither at Mr. [Josiah] Quincy’s levee, neither at any of our Classmates’ evening entertainments, did I find you, though for the purpose of taking a farewell, and leaving you some memento of an old chum, as well as on matters of business, I much wished to see your face once more. Of course you must be present at our October meeting,—notice of the time and place for which will be given in the Newspapers. I hear that you are comfortably located, in your native town, as the guardian of its children, in the immediate vicinity, I suppose, of one of our most distinguished Apostles of the Future—R. W. Emerson, and situated under the ministry of our old friend Rev Barzillai Frost, to whom please make my remembrances. I heard from you, also, that Concord Academy, lately under the care of Mr Phineas Allen of Northfield, is now vacant of a preceptor; should Mr. [Samuel] Hoar find it difficult to get a scholar—college-distinguished, perhaps he would take up with one, who, though in many respects a critical thinker, and a careful philosopher of language among other things, has never distinguished himself in his class as a regular attendant on college studies and rules, if so, would you do me the kindness to mention my name to him, as of one intending to make teaching his profession, at least for a part of his life. If recommendations are necessary, President Quincy has offered me one, and I can easily get others. My old instructor Mr [Daniel] Kimball gave, and gives me credit for having quite a genius for Mathematics, though I studied them so little in College, and I think that Dr. [Charles] Beck will approve me as something of a Latinist.—I did intend going to a distance, but my father’s and other friends’ wishes, beside my own desire of a proximity to Harvard and her Library, has constrained me. I have had the offer and opportunity of several places, but the distance or smallness of salary were objections. I should like to hear about Concord Academy from you, if it is not engaged. Hoping that your situation affords you every advantage for continuing your mental education and development I am

with esteem & respect

Yr classmate & friend

James Richardson Jr

P.S. I hope you will tell me something about your situation, state of mind, course of reading, &c; and any advice you have to offer will be gratefully accepted. Should the place, alluded to above, be filled, any place, that you may hear spoken of, with a reasonable salary, would perhaps answer for your humble serv’t

—R—

Thoreau writes in his journal on 29 October:

“Here,” I exclaimed, “stood Tahatawan; and there.” (to complete the period) “is Tahatawan’s arrowhead.”

We instantly proceeded to sit down on the spot I had pointed to, and I, to carry out the joke, to lay bare an ordinary stone which my whim had selected, when lo! the first I laid hands on, the grubbing stone that was to be, proved a most perfect arrowhead, as sharp as if just from the hands of the Indian fabricator!!!

Thoreau writes to Henry Vose:

You don’t know how much I envy you your comfortable settlement—almost sine-cure—in the region of Butternuts. How art thou pleased with the lay of the land and the look of the people? Do the rills tinkle and fume, and bubble and purl, and trickle and meander as thou expectedest, or are the natives less absorbed in the pursuit of gain than the good clever homespun and respectable people of New England?

I presume that by this time you have commenced pedagogueizing in good earnest. Methinks I see thee, perched on learning’s little stool, thy jet black boots luxuriating upon a well-polished fender, while round thee are ranged some half dozen small specimens of humanity, thirsting for an idea:

Oh who would a schoolmaster be?

I received a catalogue from Harvard, the other day, and therein found Classmate [Samuel Tenney] Hildreth set down as assistant instructor in Elocution, Chas Dall divinity student—[Manlius Stimson] Clarke and [Richard Henry] Dana law d[itt]o, and C. S. W[heeler] resident graduate. How we apples Swim! Can you realize that we too can now moralize about College pranks, and reflect upon the pleasures of a college life, as among the things that are past? Mays’t thou ever remember as a fellow soldier [in] the campaign of 37

Yr friend and classmate

Thoreau

PS I have no time for apologies

Vose replies on 22 October.

Thoreau starts his journal:

Butternuts, N.Y. Henry Vose writes to Thoreau in reply to his letter of 13 October:

I received by yesterday’s mail your favor of the 13th. with great pleasure, and proceed at once to indite you a line of condolence on your having nothing to do. I suspect you wrote that letter during a fit of ennui or the blues. You begin at once by expressing your envy of my happy situation, and mourn over your fate, which condemns you to loiter about Concord, and grub among clamshells. If this were your only source of enjoyment while in C. you would truly be a pitiable object. But i know that it is not. I well remember that “antique and fishlike” office of Major Nelson, [to whom and Mr Dennis and Bemis, and J Thoreau I wish to be remembered]; and still more vividly do I remember the fairer portion of the community in C. If from these two grand fountainheads of amusement in that ancient town, united with its delightful walks and your internal resources, you cannot find an ample fund of enjoyment, while waiting for a situation, you deserve to be haunted by blue devils for the rest of your days.

I am surprised that, in writing a letter of two pages and a half to a friend and “fellow soldier of the -37th” at a distance of 300 miles, you should have forgotten to say a single word of the news of C. In lamenting your own fate you have omitted to even hint at any of the events that have occurred since I left. However this must be fully rectified in your next. Say something of the Yeoman’s Gazette and of the politics of the town and county, of the events, that are daily transpiring there, &c.

I am sorry I know of no situation whatever at present for you. I, in this little, secluded town of B. am the last person in the world to hear of one. But If I do, you may be assured that I will inform you of it at once, and do all in my power to obtain it for you.

With my own situation I am highly pleased. My duties afford me quite as much labor as I wish for, and are interesting and useful to me. Out of school hours I find a great plenty to do, and time passes rapidly and pleasantly.

Please request friend W. Allen to drop me a line and to inform of his success with his school. You will please excuse the brevity of this: but as it is getting late, and everybody has been long in bed but myself, and I am deuced sleepy I must close. Write soon and long, and I shall try to do better in my next.

Yours truly,

Henry Vose.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

So this constant abrasion and decay makes the soil of my future growth. As I live now so shall I reap. If I grow pines and birches, my virgin mould will not sustain the oak; but pines and birches, or, perchance, weeds and brambles, will constitute my second growth.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

So when thick vapors cloud the soul, it strives in vain to escape from its humble working-day valley, and pierce the dense fog which shuts out from view the blue peaks in its horizon, but must be content to scan its near and homely hills.

Please you, let the defendant say a few words in defense of his long silence. You know we have hardly done our own deeds, thought our own thoughts, or lived our own lives, hitherto. For a man to act himself, he must be perfectly free; otherwise, he is in danger of losing all sense of responsibility or of self-respect. Now when such a state of things exists, that the sacred opinions one advances in argument are apologized for by his friends, before his face, lest his hearers receive a wrong impression of the man,—when such gross injustice is of frequent occurrence, where shall we look, & not look in vain, for men, deeds, thoughts? As well apologize for the grape that it is sour,—or the thunder that it is noisy, or the lightning that it tarries not. Farther, letterwriting too often degenerates into a communing of facts, & not of truths; of other men’s deeds, & not our thoughts. What are the convulsions of a planet compared with the emotions of the soul? or the rising of a thousand suns, if that is not enlightened by a ray?

Your affectionate brother,

Henry

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes to his brother John:

The hearts of the Lee-vites are gladdened—the young Peacock has returned to his lodge by Nawshawtuck. He is the medicine of his tribe, but his heart is like the dry leaves when the whirlwind breathes. He has come to help choose new chiefs for the tribe in the great council house when two suns are past.—There is no seat for Tahatawan in the council-house. He lets the squaws talk—his voice is heard above the warwhoop of his tribe, piercing the hearts of his foes—his legs are stiff, he cannot sit.

Brother, art thou waiting for spring that the geese may fly low over they wigwam? Thy arrows are sharp, thy bow is strong. Has Anawan killed all the eagles? The crows fear not the winter. Tahatawans eyes are sharp—he can track a snake in the grass, he knows a friend form a foe—he welcomes a friend to his lodge though the ravens croak.

Brother hast thou studied much in the medicine books of the Pale-Faces? Dost thou understand the long talk of the great medicine whose words are like the music of the mocking bird? But our chiefs have not ears to hear him—they listen like squaws to council of old men—they understand not his words. But Brother, he never danced the war-dance, nor heard the warwhoop of his enemies.

He was a squaw—he staid by the wigwam when the braves were out, and tended the tame buffaloes.

Fear not, the Dundees have faint hearts, and much wampum. When the grass is green on the great fields, and the small titmouse returns again we will hunt the buffaloe to gether.

Our old men say they will send the young chief of the Karlisles who lives in the green wigwam and is a great medicine, that his words may be heard in the long talk which the wise men are going to hold at Shawmut by the salt-lake. He is a great talk—and will not forget the enemies of his tribe.

14th Sun.

The fire has gone out in the council house. The words of our old men have been like the vaunts of the Dundees. The Eaglebeak was moved to talk like a silly Pale-Face, and not as becomes a great war-chief in a council of braves. The young Peacock is a woman among braves—he heard not the words of the old men—like a squaw, he looked at his medicine paper. The young chief of the green wigwam has hung up his moccasins, he will not leave his tribe till after the buffaloe have come down on to the plains.

Brother this is a long talk—but there is much meaning to my words. they are not like the thunder of canes when the lightening smites them.

Brother I have just heard thy talk and am well pleased thou are getting to be a great medicine.

The Great Spirit confound the enemies of thy tribe.

Tahatawan

his mark

Publisher’s rendition of Thoreau’s sketch (The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, 18)

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

The snow gives the landscape a washing-day appearance,—here a streak of white, there a streak of dark; it is spread like a napkin over the hills and meadows. This must be a rare drying day, to judge from the vapor that floats over the vast clothes-yard.

A hundred guns are firing and a flag flying in the village in celebration of the whig victory. Now a short dull report,—the mere disk of a sound, shorn of its beams,—and then a puff of smoke rises in the horizon to join its misty relatives in the skies.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

The Yeoman’s Gazette publishes Thoreau’s obituary for Anna Jones:

When a fellow being departs for the land of spirits, whether that spirit take its flight from a hovel or a palace, we would fain know what was its demeanor in life—what of beautiful it lived.

We are happy to state, upon the testimony of those who knew her best, that the subject of this notice was an upright and exemplary woman, that her amiableness and benevolence were such as to win all hearts, and, to her praise be it spoken, that during a long life, she was never known to speak ill of any one. After a youth passed amid scenes of turmoil and war, she has lingered thus long amongst us a bright sample of the Revolutionary woman. She was as it were, a connecting link between the past and the present—a precious relic of days which the man and patriot would not willingly forget.

The religious sentiment was strongly developed in her. Of her last years it may truly be said, that they were passed in the society of the apostles and prophets; she lived as in their presence; their teachings were meat and drink to her. Poverty was her lot, but she possessed those virtues without which the rich are but poor. As her life had been, so was her death.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

The branches and taller greasses were covered with a wonderful ice-foliage, answering leaf for leaf to their summer dress. The centre, diverging, and even more minute fibres were perfectly distinct and the edges regularly indented.

These leaves were on the side of the twig or stubble opposite to the sun (when it was not bent toward the east), meeting it for the most part at right angles, and there were others standing out at all possible angles upon these, and upon one another.

It struck me that these ghost leaves and the green ones whose forms they assume were the creatures of the same law. It could not be in obedience to two several laws that the vegetable juices swelled gradually into the perfect leaf on the one hand, and the crystalline particles trooped to their standard in the same admirable order on the other.

The river, viewed from the bank above, appeared of a yellowish-green color, but on a nearer approach this phenomenon vanished; and yet the landscape was covered with snow.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Prick forth the aery knights, and couch their spears,

Till thickest legions close.”

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

I noticed also that where the ice in the road had melted and left the mud bare, the latter, as if crystallized, discovered countless rectilinear fissures, an inch or more in length—a continuation, as it were, of the checkered ice.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes in his journal:

In the side of the high bank by the Leaning Hemlocks, there were some curious crystallizations. Wherever the water, or other causes, had formed a hole in the bank, its throat and outer edge, like the entrance to a citadel of the olden time, bristled with a glistening ice armor. In one place you might see minute ostrich feathers, which seemed the waving plumes of the warriors filing into the fortress, in another the glancing fan-shaped banners of the Lilliputian host, and in another the needle-shaped particles, collected into bundles resembling the plumes of the pine, might pass for a phalanx of spears. The whole hill was like an immense quartz rock, with minute crystals sparkling form innumerable crannies. I tried to fancy that there was a disposition in these crystallizations to take the forms of the contiguous foliage.

Thoreau writes in his journal:

Thoreau writes to Orestes Brownson:

I have never ceased to look back with interest, not to say satisfaction, upon the short six weeks which I passed with you. They were an era in my life—the morning of a new Lebenstag. They are to me as a dream that is dreamt, but which returns from time to time in all its original freshness. Such a one as I would dream a second and a third time, and then tell before breakfast.

I passed a few hours in the city, about a month ago, with the intention of calling on you, but not being able to ascertain, from the directory or other sources, where you had settled, was fain to give up the search and return home.

My apology for this letter is to ask your assistance in obtaining employment. For, say what you will, this frostbitten ‘forked carrot’ of a body must be fed and clothed after all. It is ungrateful, to say the least, to suffer this much abused case to fall into so dilapidated a condition that every nothwester may luxuriate through its chinks and crevices, blasting the kindly affections it should shelter, when a few clouts would save it. Thank heaven, the toothache occurs often enough to remind me that I must be out patching the roof occasionally, and not be always keeping up a blaze upon the hearth within, with my German and metaphysical cat-sticks.

But my subject is not postponed sine die. I seek a situation as teacher of a small school, or assistant in a large one, or, what is more desirable, as private tutor in a gentleman’s family.

Perhaps I should give some account of myself. I would make education a pleasant thing both to the teacher and the scholar. This discipline, which we allow to be the end of life, should not be one thing in the schoolroom, and another in the street. We should seek to be fellow students with the pupil, and we should learn of, as well as with him, if we would be most helpful to him. But I am not blind to the difficulties of the case; it supposes a degree of freedom which rarely exists. It hath not entered into the heart of man to conceive the full import of that word—Freedom—not a paltry Republican freedom, with a posse comitatus at his heels to administer it in doses as to a sick child—but a freedom proportionate to the dignity of his nature—a freedom that shall make him feel that he is a man among men, and responsible only to that Reason of which he is a particle, for his thoughts and his actions.

I have even been disposed to regard the cowhide as a nonconductor. Methinks that, unlike the electric wire, not a single spark of truth is ever transmitted through its agency to the slumbering intellect it would address. I mistake, it may teach a truth in physics, but never a truth in morals.

I shall be exceedingly grateful if you will take the trouble to inform me of any situation of the kind described that you may hear of. As referees I could mention Mr [Ralph Waldo] Emerson—Mr [Samuel] Hoar—and Dr [Ezra] Ripley.

I have perused with pleasure the first number of the ‘Boston Review.’ I like the spirit of independence which distinguishes it. It is high time that we knew where to look for the expression of American thought. It is vexatious not to know beforehand whether we shall find our account in the perusal of an article. But the doubt speedily vanishes, when we can depend upon having the genuine conclusions of a single reflecting man.

Excuse this cold business letter. Please remember me to Mrs Brownson, and dont forget to make mention to the children of the stern pedagogue that was—

[Sincerely and truly yours,

Henry D. Thoreau.]

P.S. I add this postscript merely to ask if I wrote this formal epistle. It absolutely freezes my fingers.

“Brownson was a vigorous and aggressive minister who believed that moral reform should be accompanied by political reform. Without, he affirmed, changing his basic position, he went through several religious conversions before ending as a Roman Catholic. He was a social radical in his early thirties when Thoreau came to stay at his house late in 1835. Thoreau had been allowed a brief leave of absence from his studies at Harvard that he might teach school for a term and make a little money. Brownson was living in Canton, Massachusetts, and Thoreau was sent there to see about an opening. He was interviewed and recommended by Brownson, whose children were attending the Canton school, and Brownson liked him so well that he took him into his home.”

Thoreau writes in his journal: