What made Concord a special place?

Writing in his journal on December 5, 1856, Thoreau expressed his high opinion of Concord, “I have never got over my surprise that I should have been born into the most estimable place in all the world, and in the very nick of time, too” (160).

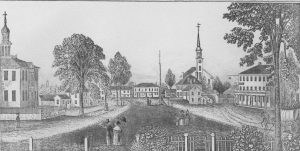

Though many of his contemporaries were moving west to explore the unknown and wild frontier, Thoreau chose to stay in the town where he had been born. Concord, Massachusetts, in the mid-1800s was inhabited by an exceptional community of scholars and writers. Some of the noteworthy townspeople included: Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Transcendentalist thinker and writer of “Self-Reliance” and “Nature”; Bronson and May Alcott and their daughter Louisa May, author of Little Women; Margaret Fuller, journalist and women’s rights advocate; and Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of The Scarlet Letter. Not surprisingly, the town had an active intellectual life, including the Lyceum lecture series and the small circulating “Concord Social Library.” Concord is also a short train ride way from the cultural center of Boston and Thoreau’s alma mater, Harvard College. Emerson would sometimes bring visitors out from the city to entertain at his house in Concord, and Henry often attended the gatherings.

Even before Thoreau’s time, Concord was rich in history. It was established in the year 1635 as the first inland English settlement, twenty 20 miles from the coast. On April 19, 1775, the first battle of the American Revolutionary War began on the battlefield of Concord. Over 60 years later, Emerson wrote “Concord Hymn,” a poem that first called the historic event “the shot heard ’round the world.”

Where and what is Walden Pond?

Where and what is Walden Pond?

Walden Pond, a small glacial lake located just two miles outside the village of Concord, gave inspiration to Thoreau every day for the two years, two months and two days that he lived there. The pond, half a mile wide and three-fourths of a mile long, is exceptionally deep and clear. It is surrounded by hills and a mixed woodland forest comprised mostly of white pine and oak trees, which Thoreau believed to be fed by “a perennial spring…without any visible inlet or outlet except by the clouds and evaporation” (195; “The Ponds”).

Walden Pond is one of several similar ponds or small lakes in Concord. It is not an exceptional pond in any of its inherent characteristics, but is only remarkable because people have made it so. Much of New England is littered with lakes formed as the glaciers in the last Ice Age receded and left depressions in the Earth’s surface from large, heavy sections of ice. As the glaciers shrank away, debris such as sand and smooth-worn stones were left in their wakes, forming attractive sandy beaches on Walden Pond on the one hand, and deteriorating the quality of land for farming on the other.

There are three hypotheses for how Walden Pond received its name. In one version, the physical description of the pond as being “walled in” slurred to form one word. In another story, the name comes from the German word for wooded, which is “bewaldet.” It is also possible that Walden is an English family name bestowed on the pond by some earlier neighbors.

Walden Pond also held some commercial significance for the nearby people. In winter, the thick layer of ice covering the pond was broken up and carted away for sale in town. The woods surrounding the pond were also a source of timber for Concord residents. Thoreau describes the ice-cutters in Walden in the chapter “The Pond in Winter,” and his interaction with a woodchopper in “Visitors.”

How did Thoreau choose Walden?

How did Thoreau choose Walden?

As a college student, Henry spent one of his summer vacations living at Flint’s Pond with his friend Charles Wheeler. The friends lived in a small cabin and slept on bunks of straw for six weeks. They were not isolated, however, for they stayed close to the rest of the Wheelers and ate all of their meals with the family. Henry and Charles passed the time reading, sleeping and relaxing. Thoreau cherished this vacation and would later return to it as inspiration for moving to Walden Pond and building a small house in the woods.

Initially, Thoreau imagined a variety of sites for his cabin, such as Fairhaven Hill by the Sudbury River, but eventually settled on Walden Pond. Though Walden Pond was not very good for fishing and the scenery around it, though beautiful, did “not approach to grandeur,” Thoreau was impressed with the pond’s depth and clarity (195; “The Ponds”). Unlike some of the nearby, muddier ponds, Walden Pond was so clear that one could see all the way to its bottom through 30 feet of water. The pond was so unusually deep that local legend held that at the center it had no bottom at all. Although Thoreau took a practical approach and measured the deepest point at 102 feet, he was still “thankful that this pond was made deep and pure for a symbol,” continuing, “While men believe in the infinite some ponds will be thought to be bottomless” (316; “The Pond in Winter”).

Henry Thoreau’s friend Ralph Waldo Emerson had purchased some 11 acres in the woods surrounding Walden Pond on a site he frequently visited, presumably to save the trees from being cut down and to construct a small building as his own study. Emerson agreed to let Thoreau live on his land in exchange for building the house, which Emerson could later use as his study. Henry now had the place he needed to try out his experiment in a simple way of living.

How did Thoreau select the site for his house?

How did Thoreau select the site for his house?

No one knows for sure why Henry chose the specific site that he did to build his cabin, although there were many practical reasons for him to do so. Most importantly, it was next to the pond, which he observed daily and in which he also bathed and fetched water for drinking. The site was also near several other locations of importance, such as the road to Concord Village, his bean field and Brister’s Spring, a source of cool water on hot summer days. The site carried other advantages such as comparatively few trees to fell, level ground, elevation from floods and a view facing south, which warmed the house and sheltered it from winter storms.

In the second chapter of Walden, Henry described “Where I Lived and What I Lived For,” writing,

I was seated . . . so low in the woods that the opposite shore, half a mile off, like the rest, covered with wood, was my most distant horizon . . . it impressed me like a tarn [small mountain lake with steep banks] high up on the side of a mountain, its bottom far above the surface of other lakes, and, as the sun arose, I saw it throwing off its nightly clothing of mist, and here and there, by degrees, its soft ripples or its smooth reflecting surface was revealed, while the mists, like ghosts, were stealthily breaking up of some nocturnal conventicler. The very dew seemed to hang upon the trees later into the day than usual, as on the sides of mountains. (95-6; “Where I Lived and What I Lived For”).

Works Cited

Thoreau, Henry David. “V: December, 1856.” The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau: Journal, IX, edited by Bradford Torrey. Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1906.

—. “The Ponds.” The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau. Walden ed., Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1906.

—. “The Pond in Winter.” The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau. Walden ed., Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1906.

—. “Where I Lived and What I Lived For.” The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau. Walden ed., Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1906.