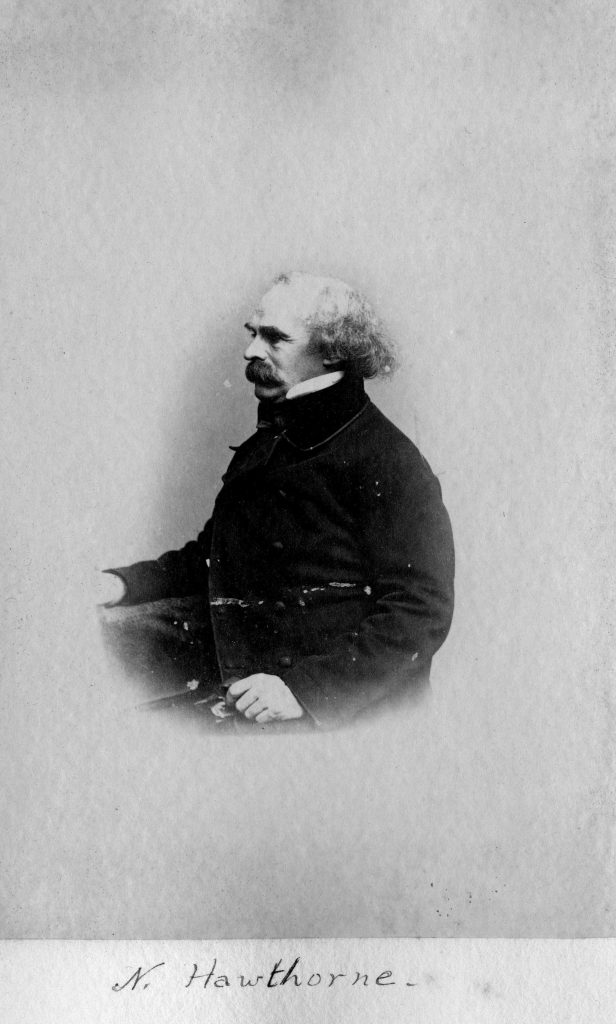

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born twenty-seven years after the United States, on July 4th, 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts. It would take him a few years to figure out that the fireworks on his birthday were not in his honor.

Although he would never consider himself a transcendentalist, Hawthorne began moving in transcendental social circles when he joined the utopian community Brook Farm in April 1841. Hawthorne was then engaged to Sophia Peabody and hoped that he would find a place they could make a life together at Brook Farm. That was not the case. After a few months at Brook Farm, Hawthorne left, after finding he could not focus on his writing.

Within a year of leaving Brook Farm, Hawthorne married Sophia Peabody and moved into the Old Manse in Concord. Thoreau had planted a garden at the house before the couple moved in. The Hawthornes quickly became acquainted with their neighbors, Emerson, Thoreau, and Alcott.

Shortly after moving to Concord, Hawthorne took a ride in Thoreau’s boat. Thoreau managed the boat well and revealed he had learned by watching Native Americans in their canoes. The boat had been built by Thoreau and his brother John and was named the Musketaquid—the name the Natives had given to the Concord River. By the end of the boat ride, Hawthorne had bought the Musketaquid off Thoreau who was in need of money. The next day, Hawthorne got a paddling lesson from Thoreau. In his journal, Hawthorne wrote, “My little wife…cannot feel very proud of her husband’s proficiency. I managed, indeed, to propel the boat by rowing with two oars; but the use of the single paddle is quite beyond my present skill.”

During their first winter in Concord, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Thoreau, and Emerson went ice skating. Sophia Hawthorne noted,

“Henry Thoreau is an experienced skater, and was figuring dithyrambic dances and Bacchic leaps on the ice—very remarkable, but very ugly methought. Next him followed Mr. Hawthorne who, wrapped in his cloak, moved like a self-impelled Greek statue, stately and grave. Mr. Emerson closed the line, evidently too weary to hold himself erect, pitching headforemost, half lying on the air.”

Hawthorne recognized that Thoreau, thirteen years his junior, had talent. After two years in Concord, in April 1843, Hawthorne wrote to an editor in New York on behalf of his friend: “There is a gentleman in this town by the name of Thoreau, a graduate of Cambridge, and a fine scholar, especially in old English literature—but withal a wild, irregular, Indian-like sort of fellow, who can find no occupation in life that suits him. He writes; and sometimes—often, for aught I know—very well indeed.” Shortly after this letter, Thoreau told Hawthorne of his plans to move to New York. Thoreau would be serving as a tutor for Emerson’s nieces and nephews while also speaking to publishers about his writing. Upon hearing his friends plans to move away, Hawthorne lamented,

“I should like to have him remain here; he being one of the few persons, I think, with whom to hold intercourse is like hearing the wind among the boughs of a forest-tree; and with all this wild freedom, there is high and classic cultivation in him too.”

In 1845, the Hawthornes could no longer afford to rent the Old Manse and moved to Salem. The Hawthornes moved back to Concord in 1852 and lived at the Wayside, where Bronson Alcott and his family had previously lived. Thoreau and Emerson were now closer neighbors than ever.

When they returned to Concord, the Hawthorne family included son Julian in addition to their daughter Una who had been born while they were living at the Old Manse. While surveying the Wayside property, Thoreau became friends with Julian, twenty-nine years his junior, and the pair took hikes together.

Besides writing fiction, like The Scarlet Letter (1850) and The House of the Seven Gables (1851), something that set Hawthorne apart from his transcendental companions was his stance on slavery. Where Emerson and Thoreau wrote abolitionist essays and spoke out against the Fugitive Slave Act, Hawthorne did not. Hawthorne perhaps assumed that the problem of slavery would work itself out eventually.

In 1853, Hawthorne was appointed the American consul at Liverpool by his college friend, President Franklin Pierce. In 1860 Hawthorne returned to the United States, and the Wayside. Since his travels in Europe, Hawthorne rarely attended social gatherings in Concord.

After seven years apart, Hawthorne noted the changes in Emerson,

“Emerson is unchanged in aspect—at least he looks so, at a distance, but, on close inspection, you perceive that a little hoar-frost has gathered on him. He has become earthlier during these past seven years; for he puffs cigars like a true Yankee, and drinks wine like an Englishman.”

When Thoreau died in 1862, Hawthorne planned to write a story in his honor. It would serve as the preface to his novel The Dolliver Romance. A year after Thoreau’s death, Hawthorne had not made progress on the preface or the novel. He wrote to his editor, “It seems the duty of a live literary man to perpetuate the memory of a dead one, when there is such fair opportunity as in this case—but how Thoreau would scorn me for thinking that I could perpetuate him! And I don’t think so.”

Hawthorne died two years after Thoreau on May 19, 1864 in Plymouth, New Hampshire. He had been on a trip to the White Mountains with former President Pierce. The pallbearers at his funeral included Longfellow, Emerson, and Alcott. The Dolliver Romance and its preface were among works that remained unfinished when Hawthorne died. He is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord.

Selected Works:

- Grandfather’s Chair (1841)

- The Scarlet Letter (1850)

- The House of the Seven Gables (1851)

- The Blithedale Romance (1852)

- The Marble Faun (1859)

On Thoreau: